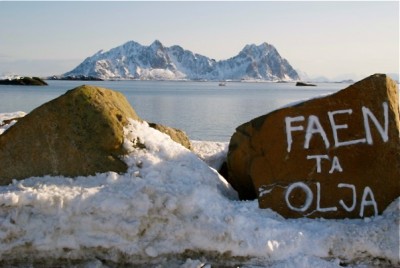

NEWS ANALYSIS: After years of trying to steer the Norwegian government away from more investment in its oil industry, because of the damage it can cause to the climate and environment, activists on both fronts are glad that at least their politicians will listen when money talks. Climate advocates are delighted that Norway’s central bank is now recommending that the country’s huge sovereign wealth fund known as the “Oil Fund” sell off its shares in oil- and gas-related companies, if only because they represent too much financial risk if oil prices dive again.

“This is a very wise proposal from Norges Bank,” said Truls Gulowsen, head of Greenpeace Norway, shortly after the central bank made its oil divestment recommendation public. The central bank is in charge of managing the Oil Fund, through its unit Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), and it’s concluded that the risks posed by the fund’s huge oil and gas stock portfolio should be reduced.

Egil Matsen, deputy chief of Norges Bank, told newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN) on Thursday that NBIM is seeking permission for oil stock divestments “because we believe it will contribute towards reducing the state’s exposure to the oil price risk.” According to Norges Bank’s analyses, the state’s collective oil price risk exposure can be reduced without much risk to the Oil Fund’s returns.

Finance Minister Siv Jensen of the conservative Progress Party, which has long been bullish on ongoing expansion of the oil industry, stated in a press release that the oil price risk issue that the central bank has taken up “is widespread and has many sides.” She stated that the recommendation from the central bank “must be handled in a thorough and good manner, such as the practice is for all important decisions” regarding management of the Oil Fund. She noted that the government is responsible for the nation’s economy and “must take a broad view on this issue.” She declined further comment.

Vidar Helgesen, Norway’s climate and environment minister from the Conservative Party, stated flat out that “the value of fossil resources will begin to decline.” He said it was important for Norway to be prepared for such a decline, but said he’d be leaving evaluation of the central bank’s request to the finance ministry. “The board of NBIM has made a purely financial evaluation of this, and they’re better at doing that than I am,” Helgesen said.

Norway’s opposition Labour Party, which also has long supported the oil industry because of the jobs it creates, seemed to embrace the central bank’s request. “There’s no doubt that Norwegian business and Norway’s financial investments are exposed to the price of oil, we saw that with the price fall in 2014,” Labour’s finance policy spokesman Trond Giske told DN. “We won’t reject the advice from Norges Bank.” He was careful to note that “this isn’t about being against or in favour of the oil industry,” but rather to address the issue of how risk must be spread. The Liberal Party, which is currently negotiating to either formally support or join the conservative government coalition, favours reducing risk of oil investments. The Christian Democrats and the Socialist Left (SV) both called the central bank’s recommendation “a step in the right direction.”

Political recognition of risks cheers climate advocates

The sheer political recognition of the risks attached to Norway’s oil investment is music to the ears of environmentalists and those trying to halt climate change. “Now Finance Minister Siv Jensen and the rest of the government must listen to the professional experts (at Norges Bank),” economist Per Espen Stoknes, who’s also a member of the Greens Party, told newspaper Dagsavisen on Friday. “If we don’t get clear signals that the government will quickly take up the Central Bank’s recommendation, the Greens will take the initiative for such a proposal in Parliament.”

Marius Holm of the environmental foundation ZERO, noted, like Greenpeace, that they’ve recommended reducing oil risk for years. “The world is changing,” he claimed, and “moving away from oil,” and then Norway should reduce its exposure to oil price fluctuations.

Gulowsen of Greenpeace noted that Norway “is already heavily invested in oil and gas resources, so selling off the oil fund’s fossil stocks will clearly help reduce our financial carbon risk.” The Greenpeace leader, who’s also been busy taking the government’s oil policy to court this week, cheered NBIM’s formal request to remove oil and gas shares from the fund’s reference index. That would, in practice, set off sales of the fund’s oil and gas shares that currently make up around 6 percent of the Oil Fund’s holdings, worth around NOK 300 billion (USD 37 billion).

The request was sent to the finance ministry because it has ultimate responsibility for the Oil Fund that’s supposed to help finance pensions for Norwegians for years to come. Although the Oil Fund is subject to guidelines for ethical investing, the central bank’s recommendation to sell off oil and gas shares is based not on the ethics of oil production in an era of climate change but purely on a financial evaluation unrelated to climate or environmental concerns. NBIM simply doesn’t seem to think oil and gas companies will be as profitable in the years to come, and that Norway’s huge investment in the oil industry (through its direct ownership stakes in offshore fields, its 67 percent stake in state oil company Statoil and the Oil Fund’s shares in other oil and gas companies) has left the country with too many eggs in one basket.

Environmental organizations like Greenpeace, Bellona, WWF, Fremtiden in våre hender (The future in our hands), Naturvernforbundet (Norway’s chapter of Friends of the Earth), ZERO and others have resorted to stressing the risky economics of oil investment themselves, after failing to curb expansion of Norway’s oil and gas industry with their anti-emission, carbon capture and other campaigns aimed at stemming climate change. Several were jubilant when Statoil’s summer drilling on controversial new oil fields in the Arctic failed to produce potentially profitable oil and gas discoveries. WWF, the Greens Party and SV have also argued that demand for oil and gas is likely to decline in the years ahead, as people become more climate conscious and electrification of vehicles shifts into high gear.

The Greens have especially argued against Norway’s tax incentives for oil companies to drill for oil and gas, with the companies able to write off up to 78 percent of their exploration costs. That also presents a risk for the state treasury if oil and gas aren’t found, or if oil fields don’t turn out to be profitable. Debate has been swirling once again this week over all the problems with the Goliat field in the Barents Sea, with new figures confirming that it’s unlikely to ever be profitable.

All comes down to money

In the end, it seems like it’s only the danger of the sheer economic risks of oil industry investment that can jerk the government to attention, whether it’s under conservative control like now or in past years when it’s been under left-center political control. Norway’s oil industry has generated far too many revenues and transformed Norway into such an affluent nation that both political camps have been reluctant to turn off the taps despite years of political rhetoric about climate and environmental concerns. Norway has long preferred to pay other countries to cut their carbon emissions, than to cut its own emissions generated by its valuable oil and gas industry.

Now top politicians, after years of creatively defending Norway’s oil industry, have woken up to the fact that its fossil fuel production probably won’t be profitable in the long run, and that economic alternatives are sorely needed. The Norwegian government recently decided against reopening its long-disputed coal mines on Svalbard and is phasing out coal operations mostly because of the low prices for coal and grim prospects for the coal industry. Now the volatile but still relatively low prices for oil are having the same effect.

Gulowsen of Greenpeace called the central bank’s request to sell off oil shares “a victory for common sense.” He noted how his organization had argued for such sales “for some time, and there is no reason why the Norwegian Ministry of Finance should not approve this request.” Norway has been over-exposed to the oil industry for far too long, he and others argue. If the government won’t stop expanding in the oil sector for climate and environmental reasons, at least it should stem expansion because of the financial risk involved.

“Recognizing the risk from unburnable carbon, Norway should also stop throwing money away on unprofitable and unburnable oil exploration in the Arctic,” Gulowsen said. That’s also part of the arguments in the court case now underway that seeks to prevent the government from continuing to grant offshore exploration licenses. While a verdict on that is expected within a few months, Jensen’s finance ministry stated that it would likely respond to the central bank by next fall.

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund