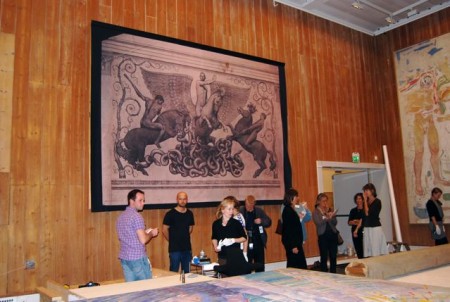

As they carefully rolled out a huge, historic canvas at the Munch Museum on Thursday, even the museum’s art experts seemed to be holding their breath. They’re about to display a large assortment of paintings and drawings by Norway’s most famous artist, Edvard Munch, many of which they’d never seen themselves.

The major exhibition opening at the museum on Oslo’s east side this weekend is being called both “daring” and “unique,” not least because it offers unique insight into how Munch worked and thought, how he revised his work, and how he often couldn’t quite decide what to do. The exhibition features around 140 paintings, drawings and lithographs that detail Munch’s seven years of preparations for what was one of the major public projects of the time: The opening and decoration of the auditorium known as the Aula at the University of Oslo in 1911.

The array of paintings and drawings on canvas and paper show how Munch created the huge murals that eventually decorated the Aula’s interior. They’d all been stashed away in storage rooms for nearly 100 years, and likely will need to be stored away again when the exhibition ends because there’s no room to keep them out on display. But they’ve been restored and will be shown at the Munch Museum through the end of the year, along with the dramatic story of how the Aula came to be after years of quarreling among officials and critics, and tough competition among artists.

Much of the never-before-seen art can be described as unfinished and experimental, even radical, but the impressive array speaks volumes about Munch’s mastery of his craft and, not least, his hard work. He created it all alone, according to the exhibition’s curators, with no assistants helping him, as was otherwise customary for famous artists working on large projects.

“When you look at the giant scale of this project, it’s really quite extraordinary,” said Patricia G Berman, a professor of art history and head of the art department at prestigious Wellesley College in Massachusetts. Berman also teaches at the University of Oslo and has been a consultant for the exhibition that Norway’s Queen Sonja will formally open on Saturday. It opens to the public on Sunday.

“The artist did everything, he was just one man doing all this,” Berman said, with perhaps one exception: “The master didn’t sew.” His housekeeper stitched two canvases together to allow Munch to work on an early version of one of the large murals, Historien.

The Aula today displays 11 finished products including the large murals Solen (The Sun), Historien (The Story) and Alma Mater, also known as Forskerne (The Researchers, depending on how many children appear in its various versions). Munch deemed all of them appropriate for display in a fashionable auditorium at a university, with a sun portraying enlightenment, a storyteller passing on knowledge from one generation to another, and a mother nurturing children. Symbolism abounds, right down to the patches (of time) on the trousers of the fisherman-storyteller in Historien, and his red cap signifying Norway’s then-newfound independence. Berman said Munch was communicating “the embodiment of Norway’s history” in Historien, with symbolism “specifically Norwegian, and universally human.”

Munch’s work unwelcome

Munch’s enormous and complicated project, though, wasn’t initially welcomed at the university. He was considered a radical and controversial artist, and he had to compete against fellow artists Eilif Peterssen, Emanuel Vigeland and Gerhard Munthe in an early round of competition in 1910. Munch and Vigeland won the first round, but political debate continued to fly over the project. When the Aula actually opened in 1911, to mark the university’s centennial at the time, no agreement on its decoration had been reached and the walls remained covered by gold tapestries for five years, according to chief conservator at the museum Ingebjørg Ydstie and curator Petra Pettersen. “Absolutely everyone had an opinion about the art,” said Ydstie. “It was a huge debate, very political.” The exhibition also shows some of Vigeland’s “losing” candidates for the Aula.

Munch ultimately prevailed after displaying the art he continued to produce for the Aula at exhibitions overseas, including Berlin. A group of his supporters ended up buying the entire Aula collection from Munch for around NOK 80,000, according to Pettersen, and the university finally accepted it as a gift. Munch’s murals were mounted in the Aula in 1916. As Berman noted, it was the height of World War I and the colourful murals and paintings offered some optimism at an otherwise bleak time. They were, in the end, generally well-received.

Now they’ve been restored as well, in connection with the university’s bicentennial celebrations going on this year. The new exhibition at the Munch Museum, entitled Munchs laboratorium – Veien til Aulaen (Munch’s Laboratory – The Path to the Aula), is the museum’s contribution to the bicentennial commemoration.

“There were so many things Munch wanted to communicate with this,” Berman said, with Ydstie noting that the exhibition of the long-stored-away art involved much research in addition to restoration. It will run until January 8, and has been supported by German firm E.ON Ruhrgas.

For more information on opening times and details of the exhibit, see the Munch Museum’s website (external link).

Views and News from Norway/Nina Berglund

Join our Readers’ Forum or comment below.

To support our news service, please click the “Donate” button now.