A new biography of Norway’s late King Olav V reflects how the country’s own royal family has also had to face the challenges of being immigrants expected to integrate. Olav underwent not only a name change but also grew up with a mother who didn’t speak Norwegian, isolated herself from Norwegian society and took him back to her homeland for long periods at a time.

All such resistance to integration is today harshly criticized by Norwegian politicians. Most demand that all resident foreigners and immigrants in Norway learn Norwegian, work to support themselves and honour Norwegian culture. Such demands didn’t seem to apply, however, to King Olav’s mother, a former British princess who’d married a Danish prince and later became Norway’s Queen Maud. She never became Norwegian herself, created her own English lifestyle in the Norwegian capital and traveled often back to England.

Her only son, baptized as Alexander Edward Christian Frederik, was also born in England. He was two years old when his father, the former Prince Carl of Denmark, famously carried him into Norway after Carl had been elected to become king of a newly independent Norway in 1905. Prince Carl became King Haakon VII, and little Alexander Edward Christian Frederik became Crown Prince (and later King) Olav V.

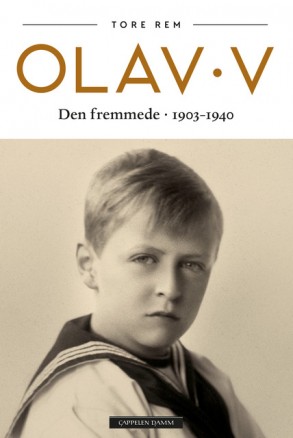

The small family of three, however, continued to speak only English at home (Maud hadn’t learned Danish either), and struggled to fit in. The first volume of the new biography of Olav V, covering the years from 1903 to 1940, is thus interestingly entitled Olav V. Den fremmede, which can either be translated to “The foreigner” or “The stranger.” Either is appropriate, after author Tore Rem and publisher Cappelen Damm opted to portray the young Crown Prince Olav as an immigrant and stranger in a strange land, over which he suddenly was destined to be monarch.

“This is the story of a foreigner, an immigrant,” writes Cappelen Damm in its own presentation of the book that’s being released this week. Rem, a professor of English-language literature at the University of Oslo who’s written several highly acclaimed biographies earlier, had also told newspaper Aftenposten when he started working on the Olav biography in 2014 that he looked forward “to bring out that sense of being foreign that characterized the first part of his life.”

The biography is “unauthorized” but Rem was given access to archives at the Royal Palace and many letters and documents that previously were unknown. They revealed a young prince “who lacked a mother,” according to the diary of Nini Roll Anker, a radical Norwegian author at the time who had married into the wealthy Anker family and whose husband Johan became young Olav’s sailing coach. Other sources noted that Queen Maud took her son along on her daily horseback rides when she was in Norway, and encourged him to be active in sports. She otherwise did what she wanted, and spent lots of time back home in England, both with and without Olav throughout her life. She also died there, in 1938.

Rem writes that young Olav’s life was also lonely, as both a foreigner and an only child who didn’t go to local schools but rather had private tutors at the palace. The royal couple (Haakon and Maud) spent time with other British citizens working at the local British legation, Rem writes. He told Aftenposten this week that “they had few Norwegian friends apart from polar explorer and hero Fridtjof Nansen,” adding that their only child’s isolation was deepened by his life at the large palace. Servants’ children were among the few he associated with, and there was even alarm that the Norwegian he did eventually start to speak was heavily influenced by a rough local dialect.

Teachers characterized him as “spoiled and conceited,” while his mother had problems putting any limits on him. Olav became “an obstinate boy” who was “extremely aware” of his position. He also grew up severely dyslectic, and had problems learning to read and write. That plagued him all his life, later making him more reserved, shy and nervous as a teenager.

The biggest task among Norwegian officials at the time was to make him “more Norwegian than Norwegians,” according to Rem’s book. The key, it was decided, would be through sports. Professionals were brought in to teach him skiing, ski jumping and sailing. Olav seemed to do well, and soon came photos of a young prince out skiing with Nansen and even his parents, and ski jumping in front of the palace. He even jumped off Holmenkollen at the age of 18, which proved to be enormously popular in the young nation of Norway. The creation of a sporty and even folksey royal image was underway.

From immigrant to refugee

Olav’s trait of having what seemed to be a nervous laugh developed into a genuine trademark, and his marriage to one of his many royal cousins, Princess Martha of Sweden, was popular as well. Rem writes that their wedding in 1929 was a turning point of sorts, making Olav more outgoing with Martha by his side. The Labour Party and working class Norwegians who opposed the monarchy at the time tried to boycott it, Rem told Aftenposten, but the royal newlyweds’ driving tour from east to west around Oslo “became a hugely important public relations victory for the royal family,” not unlike this year’s royal drive around Oslo on the 17th of May.

Subsequent tours around Finnmark in 1934 and to the US in 1939 further boosted the royal couple’s popularity, as did the arrival of their three children including Norway’s current King Harald V. “When they came back to Norway (from the US), many noted that the crown prince had changed,” Rem told Aftenposten. “He’d lost his shyness and had a new sense of self-confidence after having had to make hundreds of speeches.”

The couple also formed close ties to Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt in Washington, and that proved important given the dramatic events of 1940, when Norway was invaded by Nazi Germany and Norway’s royal family took on new roles in exile, this time as refugees. That’s likely to be picked up in the next volume of Rem’s biography.

NewsInEnglish.no/Nina Berglund