NEWS ANALYSIS: Four recent books and a new film have brought Norwegians face-to-face with one of the darkest chapters in their own history: contributing to the Holocaust. New attention on Norwegian complicity in the arrests and deportation of Norwegian Jews during World War II has implicated wartime resistance heroes and set off massive public debate.

It all led to an uncomfortable run-up to this week’s annual if digitalized Holocaust Day ceremonies. The sharp and lengthy debate over one book in particular prompted calls for a truce last month. It’s likely to resume, though, as historians argue over how much resistance heroes and even the Norwegian government in exile in London knew about the deportations in advance, and even why so few historians have researched or written about the subject over the past 78 years.

Norwegians have been coming to grips with their own Holocaust in recent years, especially after journalist and author Marte Michelet published her book Den største forbrytelsen (literally, The biggest crime) in 2014. It chronicles the treatment of Jewish Norwegians and how they were effectively registered, arrested, deported and their homes looted not just by Nazi officials but also by Norwegian bureaucrats and police. A highly acclaimed new film based on Michelet’s book was released on Christmas Day.

Historians seemed uninterested

Before that, however, little had been written and publicly distributed since Bjørn Westlie, as a journalist for newspaper Dagens Næringliv (DN), first reported in 1995 about the mass confiscation of Jewish Norwegians’ property, businesses and belongings. Westlie’s work prompted the government to form a commission charged with making amends. The commission also became plagued with internal conflict but ultimately led to the Norwegian Parliament’s recognition in 1999 of a “moral obligation” to compensate for the crimes against its Jewish population. It offered NOK 450 million to compensate survivors who were robbed of their fortunes and to fund creation of a Holocaust research center and memorial in Oslo. The Norwegian government has also officially apologized for the deportations in late 1942 and early 1943, and so has a former chief of the Norwegian police.

Since the settlement was made more than 20 years ago, however, little more has been written and widely distributed about how more than 700 Norwegian Jews were sent directly to Nazi death camps, most of them to Auschwitz, where the vast majority were killed shortly after arrival. Only around 30 survived and returned to Norway after the war along with those who had fled, mostly to Sweden, before the arrests and deportations were carried out. Once back in Norway, they found other people living in their homes, their possessions had been sold off and some were even presented with large bills for unpaid rent, taxes and electricity charges while they were gone.

That prompted publication of another new book published this week by a former member of the government commission, Berit Reisel. “I want to spark futher examination of what happened, beyond the national narrative of World War II,” Reisel told newspaper Klassekampen on Holocaust Day. Reisel, now age 75, was born in Sweden after her Jewish family had fled their home in Ås south of Oslo. She was featured in most Norwegian newspapers this week as she carried on her own campaign to make new generations aware of what happened during the war.

“The Jewish catastrophe simply wasn’t seen as part of the Norwegian war story,” Reisel told newspaper Aftenposten. “The Jews didn’t belong to the collective ‘we.'” Her own family didn’t get their home back until 1951. All their possessions were gone: “There wasn’t anything left,” she notes, which is why she has titled her book Hvor ble det av alt sammen? (What happened to it all?)

The well-organized arrests, initial confinement of Jewish men in a notorious work camp near Tønsberg and at Falstad near Trondheim, and then deportations involved scores of Norwegian police officers, brutal Norwegian prison guards and even taxi drivers hired in to transport entire families to a waiting ship, the Donau, at the harbour. Many had already been harassed for years before that. Norway had a long history of anti-semitism even before Nazi Germany invaded on April 9, 1940, and it was particularly rampant between the two World Wars.

“Anti-semitism in Norwegian society contributed towards fewer Jews being saved from the Holocaust,” wrote historian Andreas Snildal, who holds a doctorate degree in the history of anti-semitimism in Norway, in Klassekampen on Wednesday. He noted that such history hasn’t been written about very much either, but by the beginning of the 1930s, both Norwegian politicians and partisan newspapers at the time had “demonized” Jewish Norwegians, and set the stage for their tragic fate.

“We historians just simply haven’t done our job,” Eirinn Larsen, a professor at the University of Oslo, told Klassekampen last month when the latest debate about whether resistance forces overlooked threats against Jewish Norwegians reached fever pitch. She and several others blame a “patriotic” version of the war that quickly emerged right after it ended, dominated by resistance heroes and into which neither the Jews’ fate nor women’s contributions were given much if any space.

Westlie agrees that historians have been very slow, perhaps even reluctant, to research and write about Norway’s role in the Holocaust. “It’s still quite sensitive,” he told Klassekampen in November. “It’s both correct and important that we challenge the Norwegian story about the second world war.”

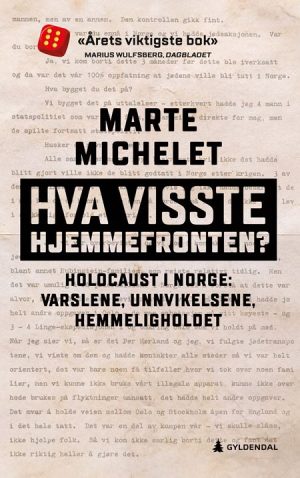

Michelet did so again, in 2018, and that’s what set off the massive, even ugly, debate that raged last fall. She wrote a second book with the question-mark title Hva visste hjemmefronten? (What did the resistance know?), and subtitled “Holocaust in Norway, Warnings, avoidance and secrecy.” It basically suggested that Norwegian resistance forces in Norway were tipped about the deportation scheduled to begin in the early morning hours of November 26, 1942, but they didn’t pass on the warnings or try to stop it in any way. The book also suggests that organized efforts to help people flee Norway and seek refuge in Sweden were profit-oriented, with Jews who escaped the Nazis and cooperative Norwegians having to pay dearly.

Reaction was swift and severe and the book remains a hot topic. Debate soared again in late October when three other Norwegian historians published their own book that bashed Michelet’s. It’s called Rapport frå ein gjennomgang av ‘Hva visste hjemmefronten’ (literally a “report” after a comprehensive review of Michelet’s book). Norwegian media widely called it an “attack” on Michelet and her book.

“It’s important that literature is critically reviewed in public,” stated the book’s three authors Elise Berggren, Bjarte Bruland and Mats Tangestuen. “Marte Michelet’s book contains a series of claims that should be examined and checked. That’s what we’ve done.”

They spent two years doing just that and came up with what they claim are “very many” errors in Michelet’s book that “undermine her central arguments and conclusions.” They also criticized Michelet for “selective” use of sources, and used more than 300 pages to challenge much of what Michelet wrote.

‘The resistance betrayed the Jews’

Michelet has vigorously defended her work as has her publishing company, Gyldendal in Oslo. “I stand firmly by my main conclusion that the resistance betrayed the Jews during the war,” Michelet told newspaper Dagsavisen. She also suggested that instead of tearing her work apart the three historians could rather have done their own research and addressed the subject in their own book.”There are still so many unanswered about the Holocaust in Norway that they could use their energy on,” Michelet said.

She also published a commentary headlined “We could have been allied” that was published simultaneously in Dagsavisen, Aftenposten, Morgenbladet, Klassekampen, Vårt Land and VG. That’s highly unusual. Meanwhile letters to editor poured in and even two prominent members of Norway’s current Jewish community landed in an argument as well. Officials at Oslo’s Resistance Museum were also upset and backed the three authors in a variety of commentaries published in local papers.

Then thing got worse when descendents of several resistance heroes also were offended by Michelet’s book, objected mightily to any tarnishing of their elders’ image and threatened to sue. They included the son of Alf T Pettersen, who ran a transport firm active in smuggling Norwegian refugees over the border, a grandson of war hero Gunnar Sønsteby and a son of resistance leader Jens Christian Hauge. They claimed it was “normal” for refugees to pay for their transport and that Jews were not “systematically” pressured. They have since backed down after discussions with publisher Gyldendal, which has supported Michelet’s book and urged dialogue with critics. Any clear errors will be corrected in new editions of the book.

Michelet, meanwhile, is preparing a new lengthy response to all the uproar over her book in an upcoming edition of the literary magazine Prosa. One thing is clear: Michelet struck a nerve in challenging what had been “established truths,” also that Norwegians were merely following Nazi orders when they rounded up more than 700 fellow Norwegians and shipped them off to Auschwitz. While Bulgaria managed to save all its Jewish citizens and Denmark did as well, notes commentator Lars West Johnsen, Norway’s Jewish community was mostly wiped out, nor did they receive much sympathy or assistance when those who survived the war returned.

The new film based on Michelet’s first book about the Jewish Norwegians’ fate, meanwhile, has received widespread attention, won strong reviews and drew the largest crowds before cinemas were shut down again because of Corona infection fears earlier this month. Its star, 35-year-old actor Jakob Oftebro, plays the son in a Norwegian Jewish family that was wiped out by the Holocaust.

He told newspaper Aftenposten that he thinks the role is “perhaps the most important I’ve had as an actor. I believe the story that the film tells really means something. What happened was so brutal, and it wasn’t so long ago.”

Oftebro said he was “shocked” over how little he knew about the Norwegian Holocaust himself. “We didn’t learn much about it in school,” he said, adding that the role of the Norwegian police in deporting the Jews “has been under-communicated.”

“We’re used to thinking that the Germans were behind it, and that’s perhaps a more comfortable thought,” Oftebro said. “We would rather talk about the resistance groups and focus on our heroes.”

NewsInEnglish.no/Nina Berglund