For most of his life, Pakistani-American Daniyal Mueenuddin had nurtured two dreams. One was to become an author. The other was to find his roots in Norway. In a strange twist of fate, he found a relative at his Norwegian publishing company, and their story speaks volumes about global immigration and how it can come full circle.

Apart from sheep and the odd hiker, no one comes by the mountain farm Busetsætra anymore. Perched on a steep hillside high above a remote valley in the county of Møre og Romsdal, its small buildings seem to be standing out of old habit, paint peeling from their cracked walls.

But on a grey, windy day recently, there were signs of life. Two men were moving around slowly, unlocking old doors with large iron keys, peeking into rooms that smelled of age, abandoned long ago.

One of these men was an author, the other one an executive at Gyldendal, one of Norway’s largest publishing firms. Professional ties, though, were not really what brought the two of them to this place most Norwegians haven’t even heard about, and with a reporter and photographer from newspaper Dagens Næringsliv in tow. Almost by accident, Daniyal Mueenuddin and Bjarne Buset had just discovered that they were related through a complex web of emigration and immigration – from Norway, to America, to Pakistan, and back to Norway.

Speaking softly and often pausing with laughter or emotion, Mueenuddin talked about his childhood’s summer holiday trips from Pakistan to a Norwegian-American immigrant home in Wisconsin, firmly run by his mother’s mother: Mormor. Those visits, he said, gave him a sense of belonging that he hadn’t really found in the two cultures that otherwise formed him: America’s and Pakistan’s.

Wide-eyed, the little Pakistani-American boy and his brother experienced a home where the floors were always spotless, the tablecloths ironed, the windows freshly polished. An elderly housemaid called Mrs. Olsen seemed to always be dusting, everywhere, even the chandeliers. The old folks would often say that things had to be done just like they had been back in “the old country.”

“The grownups spoke this foreign tongue which they called Norwegian,” Mueenuddin recalled. “Clearly, they thought it was unfortunate that my brother and I were brought up without this essential means of communication.”

Mueenuddin’s father was a Pakistani government official in the large city of Lahore. He also owned a prosperous mango farm, which Daniyal would later inherit. His mother was born in the US, into the Norwegian family that had left Norway to settle in Wisconsin.

Mueenuddin’s mother became a reporter for the Washington Post and met her future husband Ghulam, who was involved in negotiation of a water treaty between Pakistan in India, facilitated by the US government. When they married and moved to Pakistan, his mother had been relieved, Mueenuddin said.

“All these Norwegian rules she had grown up with infuriated her, so life in Pakistan was a welcome change,” he said. “If there’s one thing we do not have in Pakistan, it’s rules.”

Summers back in Wisconsin

But in the summer, when the heat and dust took a stranglehold on the Punjabi countryside, the family returned to Wisconsin for vacations.

“The airport in Madison had glass walls and everything was so clean,” said Mueenuddin. “We proceeded to this large white farm house at the end of a country road, which was very properly managed by my mormor in keeping with Norwegian custom. Her name was Dagney and she was very small, but towered over the household. Obsessed with cleanliness, she was detail-oriented and extremely conventional. The air in her kitchen was saturated with the aromas of freshly baked bread, or enormous roasts and stews.”

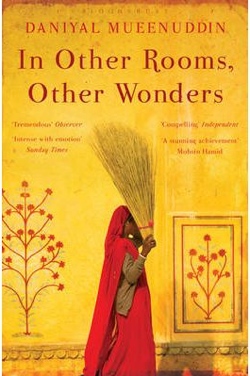

Daniyal Mueenuddin has not yet written about these things himself. Instead, his debut as an author in 2009 was a collection of short stories called In other rooms, other wonders, set in Pakistan and inspired by his childhood there.

‘Mormor’ played a formative role

But Mueenuddin insisted that the things he learned from his grandmother’s home play an important, indirect role in his book. “My encounter with her world informs me as a writer on Pakistan,” he said. “I was attracted to the mix of fastidiousness and orderliness.”

In other rooms was an immediate success, translated into several other languages. On a visit to Oslo in connection with its release in Norway, Mueenuddin met with with Janneken Øverland, head of translated literature at Gyldendal, the large publishing house. And that’s where this story becomes a case of truth being stranger than fiction. Over dinner in Oslo, Mueenuddin mentioned his grandmother, and that he had ancestors from Norway, called Buset.

“That’s funny,” Øverland reportedly replied. “I have a colleague named Buset.”

That’s how Bjarne from Lambertseter in Oslo and Daniyal from Lahore found each other across a vast distance in time as well as space. The family ties between them are thin, like twigs on two different branches of a very large family tree. Still, they’re family.

”We’ve determined that my children are femmenninger (distant cousins)of Daniyal’s,” Buset said. “He’s just 10 years younger than me, but he really belongs to the generation after me.”

After hooking up through Buset’s colleague at Gyldendal, Buset said, “I gave him two options. The minimum deal was dinner at my home. The max was a tour of Buset, and its mountain farm, and some serious hiking. He said ‘yes, please,’ all of it.”

They subsequently met in the coastal town of Ørsta and drove out along the fjord. They were not alone in the Volkswagen rental car, but also accompanied by Mueenuddin’s wife, Cecilie Brenden, a Norwegian scholar in gender studies who specializes in masculinity and honor concepts in Pakistani culture. Thus it could be said that Mueenuddin has come full circle in more ways than one.

They turned right at Vartdal, sped across the narrow valley floor of Årsetdalen, a thinly populated green crack between somber mountains topped with rotting snow. They passed abandoned farms and a few functioning ones on the way to Øye, continued to Årset, and then to Buset.

More than a century ago, Daniyal’s great-grandfather had traveled in the opposite direction. Nils Karsten Laurits Buset was born in 1860 and emigrated to America towards the end of the century. He died early, but fathered five children. One of them was Dagney, born in 1897. She had Barbara, who became the mother of Daniyal.

In a later generation, Bjarne’s father, Håkon Buset, also left the Årset valley. Rather than going to America, though, he settled in Oslo, where Bjarne grew up. But in summer, Håkon would take his family back and spend vacations at the family farm.

“Look up there,” Bjarne said, pointing to a window on the upper floor of the now-abandoned farm building. “That’s where I slept when I was here as a kid.”

Sitting on the porch of the empty house in faded yellow, they tried to imagine how things had changed since then. The barn where Bjarne played with other kids was gone. So was the hen house and the fox farm. But the family’s private blacksmith shop was still standing, its roof overgrown with moss and weed, the old anvil and a fireplace still ready for action inside.

“They did blacksmith services for the entire valley community. My dad made his own skates when he was a kid,” Buset recalled. “In winter, the fastest way to school in those days was to skate on the frozen river.”

Putting immigration in perspective

When Daniyal’s great-grandfather put his valley behind him, there was no such thing as electricity. Now people here have built their own private power plant, covering their needs and selling the excess power generated. But one feature of this landscape will never change: The shadows. When the sun shines, it shines on the Myklebust farm across the valley, while Buset sits right below the Levandehornet mountain, which steals the light. Later, Bjarne Buset and his guests would climb that mountain and look out over the fields and meadows that their ancestors had crossed for centuries.

“It’s so interesting to be here, it puts everything into perspective,” Buset noted. “There once was a level of poverty here which is so hard for us to imagine today. Perhaps it was similar to the bottomless poverty (in Pakistan) that Daniyal writes about now.”

Mueenuddin agreed. ”At first glance, it seems strange that my great-grandfather could turn his back on such beautiful land,” he said. “But when I realize how little arable land there is here, it’s easier to understand why people like him sought their fortunes in America.”

Daniyal Muenuddin is familiar with running farms and owning land. He’s a farmer on two continents, having inherited his mother’s estate in Wisconsin, and his father’s farm i Pakistan’s Punjab state, which has a reputation for growing some of the world’s tastiest mangos.

Now a modern-day owner, Mueenuddin has confronted some of the local land managers to limit their influence and regain control over what used to be a shrinking family estate. Some of the old-school land owners used to have armies of servants, sold off their land piece by piece to finance a life in luxury, and left the day-to-day business to deputies who would sometimes pocket more than they should. At the same time, the old feudal order of rural Pakistan was undermined by newcomers, men with education and smarter ways to do business.

That historic shift is at the heart of Mueenuddin’s eight interwoven short stories about various individuals in the environment of the patriarch KK Harouni – relatives, drivers, servants, mistresses – and their struggle for a better life. Most of them end up on the losing side. At the same time, the stories offer detailed, unpleasant insight into some of Pakistan’s worst problems: The breakdown of law and order, corruption, the twin curses of poverty and illiteracy, and rapid population growth.

Asked whether his stories offer any insight into why so many Pakistanis have chosen to emigrate to Norway in recent decades, Mueenuddin replied: “There are two answers to that, and they’re both true. They were given the opportunity, since Norway was rich, needed labor, and handed out visas. The bigger answer is that Norwegian generosity found its counterpart in the neediness of many Pakistanis. I believe it’s Jesus who says somewhere that if someone asked for your coat, you should also give them your cloak. Norwegians did that, and Pakistanis have been very willing to receive.”

So has Mueenuddin discussed his short-stories with Pakistani-Norwegians?

“I haven’t,” he conceded. “But since I’m telling stories from the Pakistan of the first generation of immigrants, I hope that the second and third generation will read them. And then I hope they will say, a-ha, this is what Mum and Dad have been talking about.”

For Views and News from Norway/Morten Møst

The original version of this story, written in Norwegian, appeared in Oslo-based newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (The Norwegian Business Daily) on June 23, 2012. Morten Møst donated an English version to Views and News.

Please support our news service. Readers in Norway can use our donor account. Our international readers can click on our “Donate” button: