The Norwegian Nobel Committee faces another empty chair at this year’s Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in the Oslo City Hall, but thinks it’s worth the risk. One of the three co-winners of the prize, human rights advocate Ales Bialiatski, is currently being held as a political prisoner without trial in Belarus, while others actively promote civil rights and oppose neighbouring Russia’s war on Ukraine.

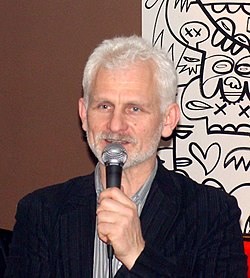

“We are urging the authorities (in Belarus) to release Mr Bialiatski,” Nobel Committee leader Berit Reiss-Andersen told Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK). Only then could he also be free to travel to Oslo to receive his Nobel Peace Prize along with the Russian human rights organzation Memorial and the Ukrainian human rights organization Center for Civil Liberties.

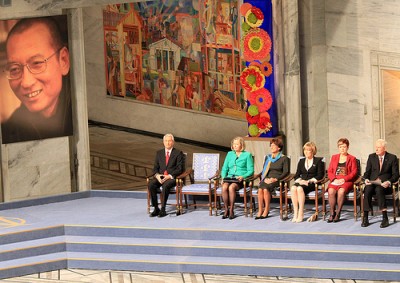

She acknowledged that there are also risks involved in awarding the Peace Prize to advocates of freedom and liberty in authoritarian countries. It took 12 years before Nobel Laureate Aung Sang Suu Kyi, who was under house arrest in Burma/Myanmar at the time, to travel to Oslo to collect her prize, and now she’s back in prison again. Chinese human rights activist Liu Xiaobo was also jailed and Chinese authorities refused to release him, too. He later died while still in custody.

Reiss-Andersen and Nobel Institute director Olav Njølstad believe, though, that brave winners of the Peace Prize “have chosen to take risks” through they very work. “We hope the prize can support the winners, and given them even more moral courage,” Reiss-Andersen told Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK).

All three winners this year were hailed for representing civil society in their home countries and promoting “the right to criticize those in power and protect the fundamental rights of citizens.” In doing so, the committe reasoned, they “have revitalized and honoured” prize benefactor Alfred Nobel’s “vision of peace and fraternity between nations, a vision most needed in the world today.”

It’s no coincidence that all three winners come from countries currently involved in or forced into deadly conflict, after Russia invaded the now-democratic Ukraine in February with cooperation from Belarus. All three new Nobel Peace Prize winners have long been involved in promoting democracy and human rights and they have challenged the authoritarian leadership of Russia, Belarus and, earlier, Ukraine.

Bialiatski, an author and literary expert in Belarus, launched his human-and civil rights work in the mid-1980s. He founded the organization Viasna (which means “Spring”) in Minsk in 1996, in response, Reiss-Andersen said, to “controversial constitutional amendments” in Belarus that gave the president “dictatorial powers” and that triggered widespread demonstrations.

Bialiatski’s organization also provided support for jailed demonstrators and their families. Viasna later evolved into a broad-based human rights organization that documented and protested the authorities’ use of torture against political prisoners. Bialiatski became one himself, jailed from 2011 to 2014 and again in 2020. “Despite tremendous personal hardship,” Reiss-Andersen said, “Mr Bialiatski has not yielded an inch in his fight for human rights and democracy in Belarus.”

The Norwegian Nobel Committee stressed how the organizations Memorial in Russia and the Center for Civil Liberties in Ukraine have long worked for the same. Memorial was founded in 1987 by human rights activists in the former Soviet Union “who wanted to ensure that the victims of the communist regime’s oppression would never be forgotten.”

Nobel Laureate Andrei Sakharov and human rights activist Svetlana Gannushikina, nominated many times for the Peace Prize herself, were among the founders of Memorial, which Reiss-Andersen said still believes that “confronting past crimes is essential in preventing new ones.” It has documented victims of the Stalinist era, compiles information on political oppression and human rights violations in Russia, and verified war crimes during the Chechen wars. The head of Memorial’s branch in Chechnya, the leader of which now supports Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine, was killed and Memorial was later branded as a “foreign agent iin Russia. Its leaders have refused to be shut down, with some operating now from an office in Germany.

The Center for Civil Liberties, meanwhile, was founded in Kyiv in 2007 as a means of advancing human rights and democracy in Ukraine. It’s been successful, only to see Ukraine invaded by Russia after its earlier government that cooperated with Putin’s was replaced. The center “has taken a stand to strengthen Ukrainian civil society and pressure the authorities to make Ukraine a full-fledged democracy,” noted the Nobel Committee. It’s currently helping to identify and document Russian war crimes against Ukraine’s civilian population.

The Nobel Committee, Reiss-Andersen said, wanted to honour these “three outstanding champions of human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence in the neighbouring countries of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. She especially hailed their “consistent efforts in favour of humanist values, anti-militarism and principles of law.”

The prize was being well-received in Norway and around the world. Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, an exiled leader of Belarus’ opposition whose husband is also in prison in Belarus, congratulated Bialiatski, calling the prize “an important recognition for all Belarusians fighting for freedom and democracy. Tsikhanouskaya, who was widely viewed as a candidate for the Peace Prize herself, also called for all political prisoners to be released “without delay.”

Leaders of other human rights organizations including Amnesty and the Helsinki Committee were jubilant, while former Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg of the Conservatives noted that she had nominated the organization Memorial for the Peace Prize several times. Audun Lysbakken, at the other end of the political spectrum as leader of Norway’s Socialist Left Party (SV), said his party had also nominated Memorial for the prize in 2020 and thought it was richly deserved by all three winners.

“The war in Ukraine and the authoritarian development in Russia is one of the biggest threats to global security for many years,” Lysbakken told NRK. “It’s an important reminder for all of us of the importance of a strong and active civil society to promote democracy and human rights.”

The prize, as always, will be awarded in Oslo on December 10, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death. It ironically was announced on Putin’s 70th birthday but Reiss-Andersen dismissed the timing as sheer coincidence. “This prize is not addressing President Putin on his birthday,” she told NRK, adding, though, that his “authoritarian government is suppressing human rights.” She stressed, though, that “we always give the prize for something, not against something.”

NewsinEnglish.no/Nina Berglund