The Oslo Stock Exchange (Oslo Børs) could mark its bicententennial on Monday by basking in both bright spring sunshine and enormous investor attention. At the ripe old age of 200, the exchange is still so active and attractive that international suitors are eagerly bidding to take it over.

As newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN) reported before the birthday celebrations began, the exchange has repeatedly renewed itself over the years. Since its opening on April 15, 1819 it’s gone from dealing with currency exchange to reflecting one of the strongest national economies in the world. That’s set off an ongoing bidding war between New York-based Nasdaq and the owner of several leading European stock exchanges, Euronext.

“Oslo Børs has always had to fight for its own relevance,” Lars Fredrik Øksendal, project leader for a new book tracking the exchange’s first 200 years, told DN. He and his fellow authors Camilla Brautaset and Gunhild J Ecklund note how Oslo Børs is one of the few national institutions set up during the years after Norway won its own Constitution that has steadily evolved and changed its role in good times and bad.

Its privatization and transformation into a stock-held entity itself in 2001 is viewed as the single most important change in Oslo Børs’ history. It’s also set off the current battle for control of the exchange by two major players, with the new book following the drama right up to January.

There’s no lack of earlier drama either in the book, with a title that describes Oslo Børs as both a “marketplace and meeting place.” It survived booms and busts, not least as Norway became a major international maritime nation and then an oil nation.

Øksendal notes how the economic upturn that began in the 1980s was different. Not only did it end with the spectacular crash in 1987 that sent exchanges diving all over the world, it marked the beginning of its role as being an important factor in how Norwegian business was financed, and thus an important part of society in general. Its powerful director at the time, Erik Jarve, seized the opportunity to promote Oslo Børs in a way that made it appeal to both industry and public authorities, winning support from the still-powerful Labour Party as well.

Jarve’ tenure also ended dramatically, when he was fired in 1994 over information regarding a blending of the exchange’s finances and his own. He committed suicide the next day. Norwegians have long been extremely cautious about situations where people are “found dead” and Øksendal acknowledges that the shocking development receives only “minimal” coverage in the book. It was difficult to avoid how the Jarve era ended in tragedy and the authors point to some of the problems that could have led to it. Øksendal argues, however, that giving the tragedy broader coverage wouldn’t have greatly increased understanding of Oslo Børs’ development over the years.

New battle for control

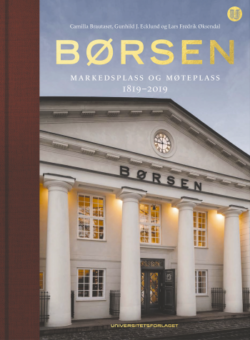

Now investors and the business world are following current developments as Euronext and Nasdaq vie to take over Oslo Børs and its modest but mighty temple-like building that was raised in 1828. The property alone, situated close to Oslo’s redeveloping eastern waterfront with a view ot the Opera House, is iconic and potentially valuable itself, while Oslo Børs’ suitors stress what goes on inside.

Euronext emerged as the first potential buyer just before Christmas, after minority shareholders had asked brokerage Carnegie to search for potential buyers. Neither Oslo Børs’ own management nor its board had been informed of what amounted to an auction process led by Carnegie, and quickly launched their own process to ensure that all potential buyers could present bids.

Nasdaq joined the bidding in late January, offering NOK 152 per share, higher than Euronext’s initial offer of NOK 145. Euronext raised its offer to 158 per share in February, valuing Oslo Børs VPS at NOK 6.8 billion. Nasdaq matched it in March, sent its high-profile chief Adena Friedman to Oslo and won the recommendations of Oslo Børs’ board and biggest shareholders, Norwegian bank DNB and pension fund KLP. Authorities have approved both Nasdaq and Euronext as worthy buyers. Norway’s finance ministry will make the final decision.

That will launch Oslo Børs into yet another phase in its development. Nasdaq controlled 37 percent of the exchange’s shares as of late last week, with Euronext holding 53 percent including preliminary acceptances. Meanwhile, King Harald was among those officially celebrating Oslo Børs’ 200-year jubilee just before this week’s Easter holidays began. There arguably was cause for jubilation, as the sturdy little building shows itself to be relevant indeed.

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund