Two Oslo-based experts on the Nobel Peace Prize have each independently selected organizations representing journalists as this year’s most worthy candidates for the Nobel Peace Prize. Press freedom and the ability to question authority, both claim, is now more important than ever in a world full of “devastating conflicts and repressive regimes.”

Henrik Urdal, director of the peace research institute PRIO in Oslo, and Asle Sveen, who co-wrote the history of the Nobel Peace Prize, met with members of Norway’s Foreign Press Association (FPA) Monday morning. Both were armed with their traditional “short lists” of those they view as the most worthy of the 318 Peace Prize candidates nominated for the prize.

Not all the nominations are known, but they include 211 people and 107 organizations, according to the Norwegian Nobel Institute, with many identified by those nominating them. Urdal and Sveen compile their lists independently of one another, and have revealed them in connection with the FPA meeting for several years.

This year they were unusually like-minded. Urdal chose the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) as his top choice for what’s often been called “the world’s most prestigious prize,” while Sveen chose Reporters Without Borders, also an international watchdog group based in France. Both Urdal and Sveen agreed that a joint prize to both organizations would be an option as well, since both have the goal of ensuring reporters’ rights to report news around the world.

The journalists, Urdal noted, “are putting their own safety at risk to provide information from the most devastating conflicts and repressive regimes.” He thinks a prize “emphasizing the importance of providing reliable information” would also be prize to those holding authorities accountable for their actions.

“Independent reporting and press freedom have not yet been the focus of the Nobel Peace Prize,” Urdal also wrote in PRIO’s more detailed announcement of Peace Prize possibilities on Monday. He firmly believes that such a prize would also stress “the importance of independent information gathering in enabling governments to make good decisions in crises and conflicts.” He noted that misinformation in wars abounds, while increasing concerns over “fake news” only make “the need for reliable, quality reporting stronger.”

Norwegians woke up Monday to hear US President Donald Trump on the radio, once again blasting The New York Times for publishing allegedly “fake news” about how little he’s been paying in taxes. Few have complained about “fake news,” or branded reports he doesn’t like as “fake news,” more than Trump, but Urdal doesn’t think even Trump could complain about a prize to recognize journalism.

Sveen and Urdal also noted how a conflict that’s broken out again between Armenia and Azerbaijan was suffering mightily this week from a lack of reliable information from the battlefields. Independent reporting and information is often, Urdal said, “the first casualty of war.”

Sending a signal

Sveen, who put Reporters Without Borders at the top of his list, also noted how more than 20 reporters have been killed this year, while others have been detained or otherwise obstructed in their work. A Nobel Peace Prize would send a signal about how important independent reporting is, not least in repressive and authoritarian regimes like China and Belarus.

“I can’t see anyone on the Nobel Committee being against a prize to journalists,” Sveen told FPA members.

Other worthy candidates in the field of journalism, PRIO noted, include Novaya Gazeta, a newspaper known for its relentless efforts to uncover corruption and human rights abuses in Russia; the Reuters reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were arrested for reporting on atrocities against the Rohingya minority in Myanman; and Can Dündar, former editor of Turkey’s secular newspaper Cumhuriyet. Press freedom has been severely restrained in Turkey in recent years, even though the country is a member of NATO.

Urdal stressed, meanwhile, that there are many worthy candidates for this year’s Peace Prize, “and that’s a good thing!” He sees no clear front-runners for the prize that will be announced in Oslo late next week, but both he and Sveen also named several other choices.

Other candidates outside journalism

Urdal’s second choice was Alaa Salah and the Forces for Freedom and Change in Sudan, followed by Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny (recently poisoned in Siberia) and the Anti-Corruption Foundation, Hong Kong pro-democracy activist Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Uighur activist Ilham Tohti in China, and young activists Hajer Sharief of Libya and Ilwad Elman of Somalia. The latter two have both been involved in peace-building efforts in their homelands.

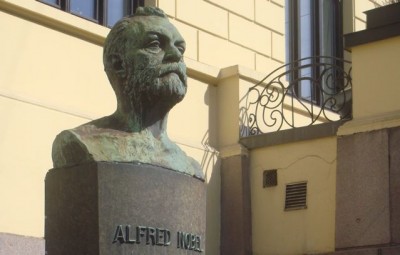

Sveen named Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg as his second most-worthy candidate, for her efforts to secure the climate. That’s directly linked, said Sveen, to prize benefactor Alfred Nobel’s desire to promote fraternity among nations in his will that funded the Peace Prize. Urdal disagreed that Thunberg would be a good choice, questioning the link between climate and conflicts.

Both think it’s unlikely the Norwegian Nobel Committee will award a new prize to any sitting politician, citing problems with recent choices in Colombia and Ethiopia. Urdal stressed his top choices aren’t meant to be viewed as predictions, rather who is most qualified in terms of their contributions to peace-making.

The Peace Prize winner is usually announced on the second Friday in October, and the prize will be awarded at a scaled-down ceremony in line with Corona virus containment measures on December 10, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death.

NewsInEnglish.no/Nina Berglund