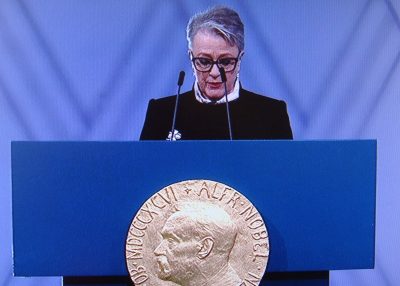

That’s the ironic headline Berit Reiss-Andersen, leader of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, jokes about seeing after newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN) revealed financial problems at the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm and the Nobel Institute in Oslo. Andersen’s biggest problem, though, is that the Norwegian Parliament seems unwilling to offer any help, even though Alfred Nobel himself put it in charge of appointing the committee that awards the Nobel Peace Prize.

“I had expected that the entire political milieu would have more respect for our independence,” Reiss-Andersen told DN, which has published several stories this week on an unfolding financial and political drama starring both the Nobel Institute and the Norwegian Parliament (Stortinget).

Reiss-Andersen, a prominent Norwegian attorney, confirmed in DN‘s first story (external link, in Norwegian) last weekend how the Nobel Institute has asked Parliament for NOK 8 million a year (USD 964,000) to help finance its operations and even allow it to remain in its historic building in Oslo. The response has been surprisingly negative, some suggest cowardly.

The Nobel Foundation, formed to administer Alfred Nobel’s will and responsible for all the Nobel prizes, has warned of financial problems for years. DN reported that more than SEK 4 billion of Alfred Nobel’s fortune was still available in 2019, when the foundation’s former leader proposed selling the old mansion that houses the Norwegian Nobel Institute. It’s costly to maintain and a sale could raise needed capital. Annual costs of selecting Nobel prize winners, the ceremonies in Stockholm and Oslo and administration, meanwhile, amount to around SEK 100 million every year.

Existing capital may be depleted within two to three years, worries Olav Njølstad, secretary for the Norwegian Nobel Committee and director of the Nobel Institute in Oslo. All five Nobel prize committees receive the same amount of money from the Nobel Foundation every year (cut to SEK 5.3 million in 2012) to finance prize work and ceremonies, but both Njølstad and Andersen contend it’s never been enough. Unfavourable currency exchange rates, higher costs in Norway and the high costs for security around Peace Prize winners mean the Norwegian committee comes out short.

Aiming to preserve their historic location

Thus the proposal to sell the iconic building and even, Reiss-Andersen warns, see the annual Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo’s City Hall moved to Stockholm where the other prizes are awarded. It’s the threatened sale of the building, though, that’s viewed as most disturbing. It’s where the winner of every Nobel Peace Prize has traditionally been selected since 1905. The Nobel Laureates also traditionally visit the Nobel Institute when they travel to Oslo for the annual Peace Prize ceremony and later, with Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa and Nelson Mandela among them. Oslo Mayor Raymond Johansen is among those calling for it to remain in the Institute’s hands, instead of being turned into, for example, a hotel.

That’s what set off what DN described as a “hidden hunt” for more money from Parliament. Njølstad and Reiss-Andersen have approached the Parliament’s administration, political leadership and elected members. After surprising confusion over how to put forth their funding request, Njølstad finally hand-delivered a letter to the Parliament’s finance committee last October. The letter described the institute’s financial challenges, how it already had cut positions and trimmed other costs. According to DN, two Nobel librarians were out weeding and planting flowers earlier this month after the gardener had to be let go.

The Parliament already allots NOK 1.5 million to the Nobel Institute to help finance its library. Members of the government, the president of the Parliament and members of the Royal Family are always in the first rows at the annual Peace Prize Ceremony in Oslo’s City Hall, and invited guests at the Nobel Banquet afterwards. For years, Norway’s foreign ministry was in charge of press accreditation for and actively involved in prize ceremony arrangements. The Norwegian Nobel Committee even used to be called Det Norske Stortings Nobelkomité (The Norwegian Parliament’s Nobel Committee).

Yet Njølstad’s and Andersen’s letter went unanswered for months. They had described how the Norwegian Nobel Institute is seriously underfinanced and how the foundation in Stockholm was calling for even more cost cuts. The Norwegian Nobel Committee warned it would be highly unfortunate for both “the country and its capital” if the Nobel Institute’s building is sold to commercial investors, and the Peace Prize ceremony moved from Oslo to Stockholm.

Njølstad and Andersen were finally tipped that their letter, somehow, had never made it to the finance committee. Njølstad quickly delivered a new copy in April. From there, however, the Norwegian Nobel Institute’s request for funds was bounced back to the administration and political leadership of the Parliament, which in turn insisted they couldn’t respond to the request. Njølstad and Andersen have been frustrated, to say the least.

Distancing the state from the prize

Given more than a century of Norwegian pride over the Nobel Peace Prize, the question arises as to why Njølstad and Andersen have subjected to such a run-around in Parliament. They’ve received conflicting information on how they even should move forward with their request for what amounts to relatively modest financial assistance.

What is clear, however, is that both the Norwegian government and Parliament have tried to distance themselves from the Nobel Peace Prize, especially since the prize in 2010 went to the then-jailed Chinese dissident Liu Xiabao. China’s authoritarian leaders responded by imposing a diplomatic freeze that didn’t melt until 2016, when Norway went along with what critics including a professor at Norway’s own military college have since called a “shameful” agreement to normalize relations. Even after that, China has snapped at any challenge to its authority and wouldn’t even grant a visa to Reiss-Andersen when she tried to attend Liu’s funeral in 2017. Only recently has Norway started to express displeasure with China over its crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong and, more recently, its alleged genocide of its Uighur minority.

DN has reported how various Members of Parliament, not least from the conservative Progress Party, have all but admitted that they don’t want to risk such a diplomatic freeze again over a Peace Prize. Asked whether it was “Liu Xiabao’s ghost” that makes it extra difficult to grant some financial assistance to the Norwegian Nobel Institute, Progress MP Morten Wold replied that “it’s at any rate an example of how great the consequences of a (Nobel Peace) prize can be. It affected Norwegian business and trade for many years.” Wold also told DN that “I don’t think there are many in Parliament who want to put forward this issue (financial aid for the Nobel Peace Prize), because there’s never been any desire to have closer ties to the Nobel Committee.”

Professor Kåre Dahl Martinsen at Forsvarets høgskole (the military college) disputes Wold’s premise that trade with China declined after the late Liu won the Peace Prize. “Wold is honest about where his priorities lie (business and trade over the values of the Peace Prize),” Martinsen wrote in a sharp commentary in DN on Wednesday. He noted, however, that Norwegian exports to China actually and steadily grew in the years after Liu’s prize was announced, up 76 percent from 2010 to 2015 according to state statistics bureau SSB (Statistics Norway).

Others have pointed to “the price of the Prize,” and rebuked MPs for not coming to its aid. The small Liberal Party, known for its outspoken criticism of Chinese leaders and their constant crackdowns on opposition, and the Center Party are currently alone in supporting some form of funding for the committee Parliament appoints. Neither the Conservatives nor Labour have wanted to express an opinion or move the issue forward, ironic since it was Labour’s former representative on the Nobel Committee, Thorbjørn Jagland, who announced and supported the prize to Liu and the Conservatives’ former foreign minister, Børge Brende, who’d nominated Liu while still an MP. “When Norway’s two steering parties are so passive, it’s difficult for the smaller parties to take the initiative,” wrote Hege Ulstein in newspaper Dagsavisen on Thursday.

‘Censoring’ the Peace Prize

Parliament President Tone Trøen, a member of the Conservatives, has also appeared unwilling to take a stand and added to the Nobel Institute’s confusion over where to apply for help. She came under heavy criticism this week from Reiss-Andersen, who told DN on Thursday that “if the Nobel Committee doesn’t get any financial support from the Parliament because of the Peace Prize to the Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, it’s a form of censorship of the Peace Prize.”

That forced a reply from Trøen, who recited the “rules” for how anyone goes about getting support from the state budget. In a commentary of her own, Trøen claimed that “financing operating costs of an external oranization” would be “an entirely new assignment for the Parliament” that requires broad political debate and support. The Parliament’s only involvement with the Nobel Peace Prize is, in her view, “to appoint the members of the Nobel Committee,” stressing that the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm is responsible for the Norwegian Nobel Institute’s financing.

“There is nothing in the statutes that say the Parliament has a responsibility for financing the Nobel Peace Prize and the Nobel Institute, also the building,” Trøen wrote. She added that she has now “guided” the Nobel Committee by recommending they take “direct contact” with the various parties represented in Parliament “to orient them” about the committee’s economic situation. Trøen, who’s recently been under heavy criticism on other matters, claimed the Parliament’s presidium (which she leads) would welcome an “open and political discussion on the financing of the Nobel Committee’s building.”

Reiss-Andersen and Njølstad don’t feel they can seek extra funding elsewhere because of potential conflicts of interest. What’s most important is the complete independence and freedom of the committee to select Peace Prize winners, in a manner that can raise no questions or doubts about the committee’s impartiality.

Neither relish approaching Members of Parliament with hat in hand, and both want to keep Norwegian politics out of any Peace Prize funding decisions. The state seems to be the only credible source of the extra funding needed that the Nobel Foundation doesn’t supply.

Hence the possible headline that a wealthy country like Norway can no longer afford, or simply won’t support, the Nobel Peace Prize that’s brought it much international attention over the years. “That would be a bitter irony,” Reiss-Andersen told DN. Parliament may ultimately regret its reluctance to help if the institute’s building is sold and the prize ceremony moved to Stockholm, but there’s little sign of any help now.

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund