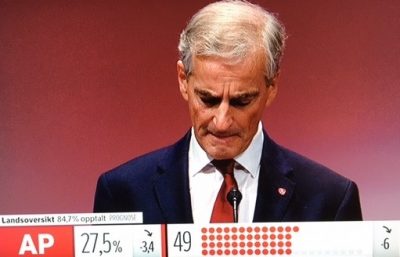

NEWS ANALYSIS: Jonas Gahr Støre was the first to admit that Norway’s parliamentary election on Monday turned into “a great disappointment,” with his Labour Party suffering its worst election results in 16 years. After initially hanging his head before unusually quiet Labour Party faithful, he claimed that “we must stand up straight” and start the work needed to win back voters.

“We need to understand, evaluate and analyze,” Støre said, to find out how the party could plunge from polls suggesting it held nearly 40 percent of the vote late last year to less than 30 percent of the actual vote. The polls themselves appear accurate, given the series of poor public opinion poll results over the past several weeks. They proved to be relatively accurate, with Labour ultimately winning just over 27 percent of the vote.

That was a disastrous result for the party that controlled Norway for decades, only occasionally lost some steam and then had a two-term grip on government power under Støre’s close friend and colleague Jens Stoltenberg from 2005 to 2013. The highly educated Støre, who had been a star of Stoltenberg’s government as Norway’s high-profile and internationally respected foreign minister, was the one chosen to replace Stoltenberg when he went on to become secretary general of NATO.

Questions were thus flying over whether Støre is the right person to lead Labour. He’s smart, speaks several languages and arguably has a stronger career CV than his successful rival for prime minister, Erna Solberg. While she’s locally educated and mostly been a professional politician in Norway, Støre studied at the prestigious Institut d’etudes politiques (Sciences Po) in Paris, the London School of Economics and Harvard, and he served as secretary general of the Norwegian Red Cross before becoming foreign minister in 2005.

The misfortunes of fortune

Støre is also a wealthy man, with an inherited family fortune that caused him trouble towards the end of the election campaign. As commentator Kjetil B Alstadheim noted in newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN), Støre seemed “surprisingly unconscious”of what it can mean to be rich.” Neither Støre nor the Labour Party apparatus around him developed a strategy for how to handle his investments, some of which collided with Labour Party principles regarding everything from social dumping to nuclear weapons.

“If he didn’t understand that questions would be raised around his private fortune, someone at Youngstorget (the Labour Party’s headquarters in Oslo) should have understood,” Alstadheim wrote as their polls slid prior to the election. “But it’s possible the apparatus didn’t have much training in such things.”

And therein lies a problem for Støre, as a wealthy and intelligent man from Oslo’s affluent west side who became the leader of a party that historically catered to the working class. “It not always easy to be rich,” Alstadheim observed, adding that it’s also “difficult to win sympathy for the problems it can cause.” Not only did they include the specific problems tied to his personal investments but they also set him apart from Labour’s constituency. Several industrial workers were quoted during the course of the campaign as saying they simply couldn’t relate to their party’s leader.

Then came all the trouble tied to Labour’s strategy of launching their election campaign with a promise to raise taxes by NOK 15 billion over the the next four years to help finance the welfare state. Even in a country where so many citizens willingly, even proudly, pay relatively high taxes, that didn’t sit well with many. Perhaps some thought Støre could afford them, but they couldn’t.

Labour has also been criticized for failing to highlight and communicate important issues for the party. The party’s campaign seized on fighting unemployment but didn’t switch strategy when unemployment started falling amidst economic recovery sparked by the conservative government’s policies. It shied away from the climate debate because the party remains so supportive of the oil industry. “That was an issue Labour didn’t dare talk about,” fumed the otherwise pro-Labour commentator Arne Strand in newspaper Dagsavisen on Tuesday. He also criticized Labour’s unsuccessful flirt with the Christian Democrats party, which is part of the non-socialist bloc in Parliament that supported the Conservatives-led government.

Strand called Labour’s defeat “a loss that really hurts in the party’s body and soul.” He added that Labour has “no one else to blame but themselves that things went so wrong.”

Triumphant incumbent Prime Minister Erna Solberg, meanwhile, claimed that “we talked about the reality that folks see. Jonas Gahr Støre has talked about a reality that doesn’t exist. Folks saw through how he tried to make things look bad in Norway, for a long time.” Voters, she claimed, “could see that unemployment went down, the waiting lists for health care services were reduced, and we’re building roads and infrastructure more quickly. When you can see such results, it’s hard to argue against them.”

Battleplan backfired

Yet that’s what Støre and Labour Party colleagues kept doing, and it backfired badly. It was Solberg and her coalition who won a vote of confidence from the voters, not Labour even though the party’s would-be govenrment partners did well. Both the Socialist Left (SV) and Center parties emerged as the election winners, but ended up losing power and influence because of Labour’s decline.

“It’s sensational that both SV and Center did well while Labour fell,” Strand wrote. “It shows that Labour lacked a clear profile and good programs.” Election researcher Bernt Aardal linked Labour’s fall to “a massive uproar” in Norway’s outlying districts against Labour and in Center’s favour, not least in Northern Norway where residents were angry that Labour went along with the government’s plan to shut down or consolidate many operations including the military air station at Andøya. In that community alone, Labour’s share of the vote dove by more than 60 points, also to the benefit of the Center Party. Labour also lost seats in Parliament in important counties like Telemark, long an industrial stalwart. Voters there also were lured away by the Center Party and its campaign against local government reform and so-called “centralization” of public services.

So now Støre and his Labour colleagues will huddle to “understand, evaluate and analze” their mistakes. “We shall carry on,” the 57-year-old Støre told his colleagues. “I’m going to carry on for several more years.” He promised to be “constructive” in opposition and he congratulated both Erna Solberg and SV and the Center Party for “a good election.”

No plans to quit

He told reporters, meanwhile, that he “took responsibility, as leader of Labour” for the election defeat and that he had no intention of stepping down. Asked whether his personal finances played a role in the defeat, he said “I don’t think so.” He said he didn’t think his leadership is under threat and that he views the party as unified.

One of his deputy leaders and potential internal rivals for party leadership, Trond Giske, seemed to agree. “The last thing we need right now is a personality conflict,” Giske told state broadcaster NRK Tuesday morning. Støre planned to meet with the party’s central board Tuesday afternoon, after finally heading home in the middle of the night where the lights were still on as he arrived.

“This will be very good,” Støre told reporters gathered outside, noting that he thought his wife Marit Slagsvold was still awake and waiting for her defeated husband. “I’m not sure there will be many words, but I think there will be a good hug. And we both need that. I’m sad and sorry (about his party’s defeat), but I can also smile because we’ll stand tall throughout this.”

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund