The Norwegian government and Oil Minister Tina Bru came under harsh criticism this week when they offered 136 new oil exploration licenses in more areas of the Arctic. The move comes while the Supreme Court and Parliament are reviewing the risks of earlier Arctic projects, and it was blasted as being both “arrogant” and “reckless.”

“This is a shameful day for Norwegians,” claimed Frode Pleym, head of Greenpeace Norway which is among the plaintiffs in the landmark “People vs Arctic Oil” case that was heard by Norway’s highest court last week.

“It feels insane to witness ostrich politics such as this from the Norwegian government,” Pleym added. “In a time of climate crisis, they choose to facilitate even more oil exploration in the vulnerable Arctic. This may even come at a huge cost to Norwegian taxpayers.”

Greenpeace described the 136 new oil licenses being offered to oil companies as “a mockery of future generations.” The organization and other climate and environmental advocates argue that not only will oil drilling and production generate more carbon emissions and risk oil spills, it can also prove costly for Norwegian taxpayers. Government tax incentives leave the state responsible for covering most of the exploration costs if insufficient reserves of oil and gas are found to warrant production. Arctic exploration and production are also much more expensive than offshore operations elsewhere, meaning some projects won’t be profitable when oil prices are below USD 50 a barrel or even more.

‘Important’ for job creation

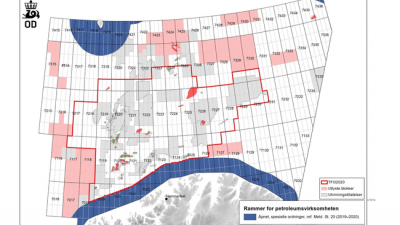

Norway’s Oil & Energy Ministry, however, claimed in a press release Thursday that it’s still “important” to examine all the areas of the Norwegian continental shelf that have been opened for petroleum activity, including lesser-known areas. Most of the new license prospects are in the Barents Sea, some of them close to the so-called “ice edge” in the northern Barents. That’s an area that’s been especially controversial and its borders were finally settled on just last summer.

Of the nine new Arctic areas open for licensing, eight are in the Barents and one is in the Norwegian Sea. Oil companies are being “invited” to apply for exploration licenses, with the state deciding which companies can explore where. Plans call for licenses to be issued during the second quarter of next year.

Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK) reported that fully 60 percent of the new exploration blocs lie in an area that the state’s own environmental directorate calls “especially valuable” for the nature and “sensitive.” Oil Minister Tina Bru of the Conservative Party insists, however, that exploration in the areas is in line with the government’s platform and the wishes of Parliament. She’s most concerned about the prospects for more economic development.

“Around 200,000 people are employed either directly or indirectly in the petroleum sector in Norway,” Bru stated. “New discoveries (of oil and gas) are crucial for ongoing activity to create ripple effects, profitable jobs, value creation in the entire country and revenues for common good.” She also insisted that petroleum operations on the Norwegian Continental Shelf have “the highest standards within health, the environment and safety. Exploration, development and operations occur with low emissions.”

(See the entire press release here, external link to the ministry’s own website.)

Her decision to move foward with Norway’s 25th licensing round was nonetheless viewed as a provocation,not least at a time when the Supreme Court is deliberating whether the 23 licensing round violates an environmentally oriented chapter in the Norwegian constitution. The Parliament’s own disciplinary committee is also currently reviewing whether critical information involving oil reserves and costs was withheld when the southeastern Barents was opened for exploration in the last left-center government.

Experts have also recommended strongly against further oil activity in the Arctic, so has a United Nations representative, and now one of the government coalition’s own members (the Christian Democrats) are coming out against it, too. Jon Christian Fløysvik at the University of Oslo’s law school called the “symbol effect” of the government’s new licensing “extremely unfortunate.”

“It can be viewed as arrogant when we’re waiting for decisions from the Supreme Court and the Parliament,” Fløysvik told NRK. “We’re talking about fundamental decisions that will affect future generations. Then (the government) should at least take the time to clarify relevant premises before inviting bids for licenses. What’s the hurry?”

Silje Lundberg of Naturvernforbund, Norway’s chapter of Friends of the Earth and also a plaintiff in in the case against Arctic oil, was furious. She called the government “frekk” (audacious) in its zeal to spur more oil activity in some of the Arctic’s most sensitive areas and her predecessor Lars Haltbrekken, now a Member of Parliament for the Socialist Left party (SV) agreed.

“The government’s oil plans amount to gambling with the climate, nature and money,” Haltbrekken said. “It’s like playing Russian roulette with important nature like fish and seabirds. Absolutely all professional environmental warnings against oil drilling here have been ignored.”

Thina Saltvedt, chief analyst for sustainable finance at large Nordic bank Nordea, noted that demand for oil between 2030 and 2035 may amount to only half of current levels. “We risk using public money that we’ll never get back,” Saltvedt said, referring to the government’s tax incentive program. “And the Barents is not one of the areas that so far has shown the best profit prospects.” Norway’s own state oil company Equinor now favours investing mostly in areas near existing infrastructure, except when the state takes on the risk of covering most exploration costs when no oil is found.

NewsInEnglish.no/Nina Berglund