NEWS ANALYSIS: Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre walked into the proverbial lion’s den on Thursday, when he addressed the Sami Parliament in Karasjok just a week after facing angry Sami demonstrators in Oslo. Støre had also just learned that his Labour Party has never been so unpopular with Norwegian voters, six months before mid-term elections in September.

Labour now holds only 15.5 percent of the vote, according to a new poll conducted by research firm Opinion for news media FriFagbevegelse, Dagsavisen and ANB. The rival Conservatives can claim 36.9 percent, roughly equal to what Labour, its government partner Center and all three of Norway’s left-wing parties can claim together.

It’s the latest evidence of a steady decline for Labour that election researcher Johannes Bergh sees no signs of ending. “Right now there are no clear signs that this will turn around (for Labour),” Bergh told FriFagbevegelse. “Voters have completely changed their opinion since the Parliamentary election a year-and-a-half ago.”

The disastrous poll figures for Labour come just as the party is under pressure to renew its own leadership, even though Støre himself appears secure in his post for lack of another prime minister candidate. The party’s election committee needs to at least come up with a candidate for a new deputy leader, and the stage is set for a potentially divisive battle for the spot.

Meanwhile Labour is already in what political commentator Lars West Johnsen calls “a deep existential crisis.” Johnsen, writing in newspaper Dagsavisen on Thursday, is clear about what’s at stake: “The future of a party plagued by a doomsday mood and which isn’t capable of emerging from its own shadow.”

The reasons for the crisis are many. After campaign promises that Labour and Center would address the needs of “ordinary people,” middle-class voters have found themselves hit by record high electricity rates, ever-rising prices and much higher taxes. Even lower-income Norwegians that Labour and Center vowed to help don’t see much relief, and lines are longer than ever at food banks and state welfare offices.

Many also believe Støre’s government keeps fumbling on efforts to provide rate relief to both households and businesses, lacks empathy for those struggling and for even a basic understanding of economics and what causes inflation. Critics have also complained that Støre’s government keeps appointing commissions to study issues and problems instead of acting on them, while the state keeps getting richer on record-high oil, gas, electricity and tax revenues and people feel poorer.

Støre and his controversial finance minister, Center Party leader Trygve Slagsvold Vedum, keep blaming all their troubles on Russia’s war on Ukraine, the ensuing energy crisis and unforeseen expenses for defense and aid to Ukraine. Critics both inside and outside the country counter that the government, however, is profiting on the war that’s sent energy prices skyrocketing, and not sharing the profits

Voters, meanwhile, appear to simply have lost confidence in Støre and most of his other government ministers. In addition to Labour’s internal leadership problems, the party has also arguably lost much of its traditional constituency of blue-collar industrial workers and voters who are members of labour organizations. There’s simply not nearly as many of them anymore, after foreign workers willing to work for lower pay took over most of the jobs in the construction trades, industrial production and service industry. They don’t vote in Norway, and those who do (not least immigrants from Poland and other former eastern bloc countries) often favour right-wing parties, not Labour.

Nowhere has the loss of confidence in Støre’s government, however, been more evident than among Norway’s indigenous Sami. They’ve long suffered discrimination and various indignities but frustration and anger hit the boiling point two weeks ago. That’s when both Sami and environmental activists lost patience with Støre’s government for not acting on a Supreme Court decision from October 2021 that state-sanctioned wind power turbines in Fosen violated the Samis’ human rights because they disturbed reindeer grazing in the area. Demonstrations ran for eight straignt days, finally resulting in an official government apology last Friday, but still no concrete plan for resolving the conflict. The Sami in Fosen want the turbines to be taken down, while the government and investors behind them claim the electricity generated by them is sorely needed and believe the reindeer and turbines can coexist.

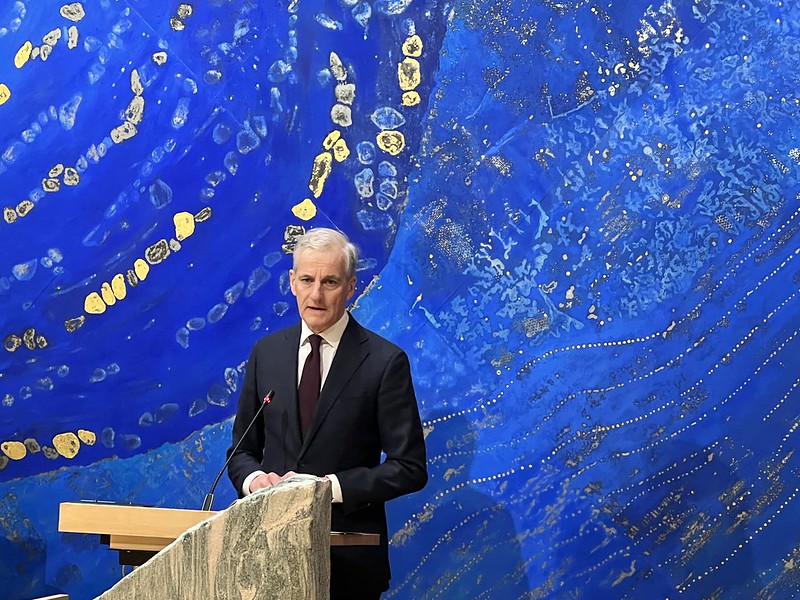

It was that uneasy truce that Støre had to handle on Thursday, when he’d long been scheduled to fly up to Norway’s northernmost county of Finnmark, address the Sami Parliament and meet with reindeer herders in Karasjok before traveling on to Alta. He was greeted by the president of Sámediggi, Silje Karine Muotka, who seemed to try to reassure the prime minister that the meetings would be cordial.

Støre addressed the recent demonstrations and hostile conflict head-on, right after opening pleasantries and stressing his “great care and respect” for the Samis’ traditional settlement region outdoors. His visit, he said, took on new meaning after the demonstrations in Oslo, and he quickly referred to how his government had apologized that government permission to build the turbines constituted a human rights violation.

“And I stress here, from the Sami Parliament’s podium,” Støre said, “that the government takes its responsibility seriously, and we will work thoroughly and as quickly as possible to follow up the Supreme Court decision. This has taken too long. We will do what we can to change that.”

Støre also said he’d been deeply moved, during a meeting in Oslo with Fosen reindeer herders last week, when one of them spoke of years of opposition from the state “that made them feel the Norwegian government wasn’t there for them, that they weren’t seen nor heard nor understood. That they stood alone, felt insecure. We can’t have that. Everyone should feel the state is fair and that our rights are respected.”

He still offered no concrete plans for resolving the conflict, though, prompting demonstrators listening to him to warn that they will return to Oslo and resume their protests if no progress is made quickly. “We will remind Støre that we won’t accept an apology unless something happens,” Elle Nystad, who was active in the Oslo demonstrations, told Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK).

Muotka said she’s glad Støre wants to improve relations between the government and the Sami, but warned that Støre’s frequent use of the word “dialogue” doesn’t erase Sami rights. “We have an ongoing consultation with the government around the Fosen case that we must conclude, and that I will secure.”

Støre started his day in Finnmark by meeting two reindeer-herding families just outside Karasjok, and discussing the challenges they face. “We talked about reindeer operation, climate change, conflicts tied to land rights and the Fosen case,” Støre said. “It was useful to hear their experiences and opinions.”

He and Muotka also had a meeting about the Fosen case, cooperation between his government and the Sami Parliament and an upcoming report aimed at reconciling generations of differences between the Sami and Norwegians. He stressed the need for more electricity, also in Finnmark, and thus the value of wind power.

“It was a good meeting and I value having right dialogue about important and demanding issues on which we will cooperate,” Støre said.

NewsinEnglish.no/Nina Berglund