Outgoing Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg spent much of the weekend in a whirl of farewell events, and he’s been packing his way out of his office, too. After eight years as one of the most well-liked premiers in Norwegian history, he was due to resign on Monday after his Labour Party won the most voters in the last election but still lost government power.

On Friday night he had a farewell dinner with his staff. On Saturday it was time for a farewell dinner with his government ministers, he told newspaper Morgenbladet. On Monday he’d be thanking his colleagues, his drivers and his bodyguards.

On Tuesday he’ll officially be back as head of the largest opposition party in Parliament. His Labour Party won just over 30 percent of the vote in the September 9 election, more than the rival Conservatives, but Labour’s two coalition partners fared badly so they collectively lost voters. In typically optimistic Stoltenberg style, though, the 54-year-old soon-to-be-ex-prime minister was upbeat and already looking forward to his new, less-demanding and, arguably, more liberating duties as parliamentary leader for Labour.

“As prime minister, I’ve been at the top of the system and had to take responsibility for all government decisions,” Stoltenberg told Morgenbladet. “Now I can show more impatience. That has its advantages. I respect the parties (the Liberals and Christian Democrats) that have entered into a cooperative agreement (with the new Conservatives-led government) and I won’t force myself on them, but if they want to cooperate (with us), we’re prepared. The Liberals and Christians Democrats can, in many areas, achieve more by cooperating with us.”

Some commentators have claimed that Stoltenberg now will do what he can to split up the non-socialist bloc, in classic “divide and conquer” style. He told newspaper Aftenposten last week that he thinks the four non-socialist parties led by the Conservatives will hang onto power through the four-year parliamentary period, “but there is much more room for negotiations and for making decisions in Parliament now.”

He jokes that he “favours a majority government when I’m in the government, and a minority government when I’m in opposition.” Even though there is agreement on many key issues between the left and right sides of politics in Norway, he still sees major differences on issues such as tax levels, whether to allow private schools, how the hospitals should be financed, how much money Norway should spend on culture, foreign aid and farming subsidies. He’s ready to challenge the new government whenever he feels the need.

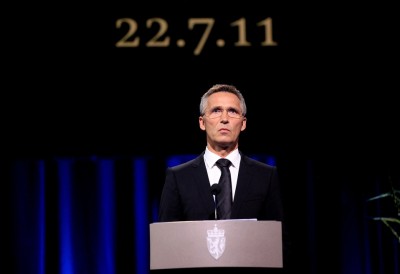

His personal charisma and popularity (“Everyone likes Jens,” one top opposition politician said recently) make him persuasive. He’s often greeted like a rock star when he strolls down an Oslo street, and he’s won the respect of world leaders US President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, and business leaders like Bill Gates. He may be best remembered for the way he led the nation through the trauma of the July 22 terrorist attacks in 2011. The overall lack of preparedness for such attacks, however, led to his government’s downfall.

Asked what he’ll remember most from his eight years in office, Stoltenberg immediately responds with “the 22nd of July, 2011 … when I realized that there’d been an explosion, and began to understand the scope of what happened on Utøya (the island where 69 mostly young members of his party were massacred by a lone gunman). People in my office building lost their lives, young Labour Party members whom I’d known for years lost their lives. There’s nothing that compares to that.” Stoltenberg’s ability to show both strength and compassion in the days and weeks that followed the attacks branded him as a “statesman” after years as a politician.

Asked what he’s most proud of after his two terms as prime minister, Stoltenberg has said it was the “fellowship that got us through the finance crisis with the lowest unemployment rate in Europe,” and that Norway has become a multi-cultural country. He’s a champion of diversity, and sees it as a national strength. He also says he’s most proud of the “fellowship” in Norway that aims to distribute income and provide for equality and fairness.

Now he and his diplomat wife Ingrid Schulerud will move out of the still-new prime minister’s residence, just behind the Royal Palace, and back to the duplex in Oslo’s Nordberg district that they’ve shared for years with Stoltenberg’s sister and her family. They intend to do some remodeling, after eight years of relative neglect, and he’ll swap his chauffeur-driven car for his bicycle to get to work, at least until the snow comes.

And then he’ll start plotting Labour’s return to government power. Arne Strand, veteran political commentator for newspaper Dagsavisen, wrote over the weekend that Stoltenberg can be the leader of the Labour Party and its candidate for prime minister for as long as he wants. He’s still relatively young and has dismissed speculation that he’ll likely accept some top international job somewhere. That can’t be ruled out, but for now he still wants to lead Norway, again.

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund