There was no lack of hyperbole when Statoil presented its latest development plan for the long-delayed Johan Castberg oil field off Northern Norway on Tuesday. Statoil has resorted to extreme cost-cutting to make it profitable, however, and North Cape communities hoping for economic development from the Castberg project may wind up disappointed.

“This is a great day for the Kingdom of Norway and the region of Northern Norway,” gushed Norway’s Oil & Energy Minister Terje Søviknes, who’s otherwise been under pressure on both the professional and personal fronts lately. He hailed Statoil and its partners in project, Italian oil company Eni and the state’s own direct oil ownership entity Petoro, for their work on the project.

“This is a great day!” agreed Statoil’s own Margareth Øvrum in the Norwegian oil company’s own announcement (external link) that it had “finally succeeded” in realizing the Castberg development. Øvrum, Statoil’s executive vice president in charge of technology, projects and drilling, called the project “a central part of the further development” of Arctic oil projects, claiming it will “create substantial value and spinoffs for Norway” for the next 30 years.

Kjell Giæver, director of a network of oil and gas industry suppliers in the region called Petro Arctic, was also jubilant. “It’s not every day those of us in Northern Norway get 500 new jobs based on competence and spread over the entire region,” Giæver told Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK). “So this is an historic day, with ripple effects of oil activity in Northern Norway and Finnmark.”

Others aren’t so sure, since Statoil not only has cut investment in the project by more than half and further delayed a decision to build a land-based terminal for Castberg’s oil just south of Honningsvåg near Norway’s famed North Cape. Community leaders and politicians farther north along the coast in Honningsvåg have long wanted to share in the economic development opportunities posed by Castberg, and have been angered when Statoil had cut back project plans on earlier occasions.

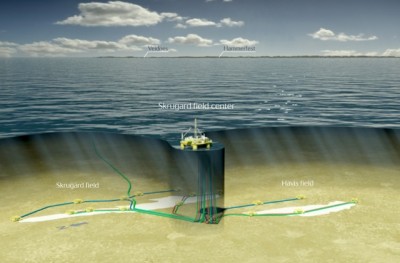

The Castberg field in the Barents Sea lies 110 kilometers northwest of the troubled Goliat field, which in turn lies 85 kilometers northwest of Hammerfest. Goliat was Norway’s first major oil and gas development in its Arctic/Barents region, and Giæver was now claiming that the new development plan for Castberg “really puts Northern Norway on the map as the gold coast of Norway.” Statoil has confirmed that the Castberg field’s supply- and helicopter base will be located in Hammerfest, while its operating organization will be based in Harstad.

The vice-mayor of Hammerfest, Marianne Sivertsen, was also “very glad that it now looks like the (Castberg) project will be realized. “That’s extremely positive and means a lot for our entire region and this part of the country,” she told NRK.

Hammerfest already serves as the base for oil and gas from Goliat, through the major Melkøya facility based on an island just off Hammerfest. Hammerfest, which has seen great economic development in recent years, is also the base for Italian oil company Eni, which operates and owns 65 percent of Goliat. Statoil owns the other 35 percent while it’s the operator of the Castberg field with a 50 percent ownership stake in the field. Eni owns 30 percent of Castberg while Petoro AS, which represents the state’s own direct ownership interest in offsore oil fields on the Norwegian continental shelf, owns 20 percent.

Statoil itself admits that the Castberg project has been riddled with “challenges” and delays because initial development plans proved unprofitable when oil prices fell below USD 80 a barrel. Now the project’s overall investment has been cut by more than half, to NOK 49 billion (USD 6 billion at current exchange rates for Norway’s weakened krone), after Statoil “worked hard” with its suppliers and partners to “find news solutions.”

That clearly involved hard bargaining on the part of Statoil and massive cost-cutting by all involved that Statoil went to great lengths to explain in its own version of the process (external link). Statoil, which now claims the project can be profitable at an oil price below USD 35 a barrel (compared to around USD 63 now), also boasted that Castberg remains the world’s biggest offshore oil and gas development to be given the go-ahead in 2017, albeit at a time of major cutbacks in the oil industry because of lower oil prices. Statoil predicted the first oil from the field will start flowing in 2022.

The total number of long-term operating jobs due to be created has also declined from levels expected in a broader area of Northern Norway earlier. Now Statoil puts them at around 1,700 full-time equivalents nationwide including 500 in Northern Norway. That’s what may disappoint the region around the North Cape the most, and officials in Honningsvåg. They’ve been lobbying for years to get Statoil to build the land-based oil terminal at Veidnes, just outside Honningsvåg, to receive oil from the Castberg field. The sheer construction of the terminal alone would provide many more jobs than the 1,800 now expected in Northern Norway during Castberg’s development phase.

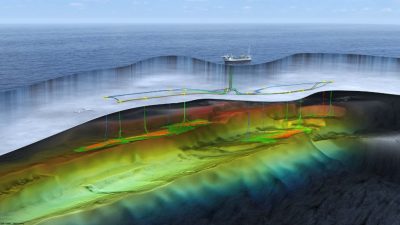

No terminal will be built any time soon, however. Statoil announced that the Castberg field will now at least initially be developed using a floating production and storage (FPSO+) vessel at the field with “additional subsea solutions.” It’s worth noting that Statoil only highlighted illustrations of the field and an FPSO+ vessel in its presentations on Tuesday, not earlier drawings of pipelines leading to a terminal near Honningsvåg.

Statoil also noted that there were “significant differences in costs between a concept based on bringing the oil to shore (near Honningsvåg) in a pipeline and a concept based on offshore oil offloading.” A terminal would likely be much more expensive and Statoil and its partners thus put off any decision to build pipelines and the terminal at Vednes. Statoil stated instead that it would “continue to work to optimize opportunities in the area and the timing of project activites.” No decision on the terminal project will be made until 2019.

Oil Minister Søviknes accepted the decision by Statoil and its partners to now evaluate the terminal near the North Cape as a separate project. Any terminal is also being viewed on the grounds that it should be able to take in oil not just from the Castberg field but from Goliat and the Alta/Gohta and Wisting fields as well. While that can pose another ominous delay for the terminal project, Søviknes called the decision “correct,” adding that the “terminal must be evaluated in a larger context.”

Giæver of the industry group Petro Arctic remained optimistic. “We have no reason to think that bad news will be coming,” Giæver told NRK. “We think this a joyful day, and a national event tied to industrial jobs, investment decisions and an outstanding project that will generate revenues and profits for everyone who lives in this country for many, many decades ahead.”

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund