A new book about convicted terrorist Anders Behring Breivik offers new answers to a question that continues to plague many Norwegians: How could their relatively peaceful and orderly society produce a mass murderer like Breivik? The book also is sparking debate over self-censorship by Norwegian media, as it presents information about Breivik’s severely troubled childhood that the media had chosen to withhold.

Newspaper Morgenbladet, among the many Norwegian media outlets devoting major coverage to the book this week, raised (and answered) another key question on Friday: “We have lived with Anders Behring Breivik every day for well over a year. Do we need 380 pages on him now? The answer is, in fact, yes.” Other commentators have agreed, calling the book “necessary” as soul-searching over Breivik’s attacks last year goes on. Some call it the most important book so far on the attacks of July 22, 2011.

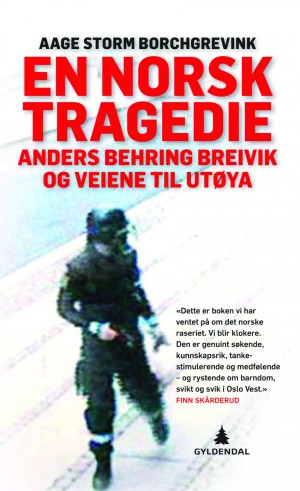

The new book, entitled En norsk tragedie (A Norwegian tragedy), deals with many aspects of the attacks, not least what happened on the island of Utøya where Breivik gunned down 69 persons after bombing government headquarters in Oslo.

The most controversial portions, though, delve into an aspect of Breivik’s background that most Norwegian media have opted to ignore: His childhood with a struggling divorced mother living on Oslo’s otherwise affluent west side. Publishing firm Gyldendal and author Aage Storm Borchgrevink, a senior adviser at a leading human rights organization who also has written books about conflicts in the Balkans and the Caucasus, dared to do what no other Norwegian journalist or writer had: Disclose information Borchgrevink collected after poring over psychiatric evaluations of Breivik when he was just three-four years old, studying court records of custody battles between Breivik’s divorced parents and interviewing witnesses to Breivik’s early childhood. They confirmed medical experts’ evaluations that Breivik suffered from grov omsorgsvikt, literally a severe lack of childcare from responsible adults that may well have led to the hate, anger and lack of empathy that characterize him as an adult.

Critics don’t brand the book as simply an attempt to “blame the mother,” though. Rather, the book is being widely praised as a detailed, sober, comprehensive effort to explain how Breivik became the man he did. “Our understanding of the terrorist needs this,” wrote Jo Moen Bredeveien, editor of Magasinet Plot. Borchgrevink’s book suggests that Breivik failed to receive the care he should have from either his parents or responsible public authorities.

Some media continue to refrain, out of consideration for Breivik’s mother’s privacy, from publishing the details in Borchgrevink’s book about how she had trouble rearing him. The book seems to have emboldened others to do so, though, for the first time. A-magasinet, the weekly magazine published by newspaper Aftenposten, opted, for example, in its Friday issue to reprint excerpts from the book based on reports from the state’s center for child- and youth psychiatry (SSBU), where Breivik’s mother sought help in 1983. They reveal how Breivik’s mother began viewing her son as difficult even before he was born, because of how he kicked during her pregnancy. SSBU experts viewed her as “unstable,” noting how from infancy, she alternately embraced and rejected Breivik, according to the book, even revealing “death wishes” about him. Her own psychiatric problems made her unable to care for her son, and doctors believed he suffered from a lack of bonding to a primary caregiver, usually the mother, even as a baby. A-magasinet also cited, for example, the book’s report that Breivik “lacked fundamental safety and security and was poorly bonded,” according to one psychologist at SSBU. Breivik, the book suggests, grew up confused and highly insecure during his most formative years.

‘Careful’ media

Borchgrevink told newspaper Dagsavisen on Friday that he’s “frankly surprised” so little information about Breivik’s childhood has been published before now. “I wanted to find out where his hate came from,” he said. He thought Breivik was “a typical example of Internet radicalism,” whose extreme right-wing views and hatred for non-ethnic Norwegians in Norway were fed by other racists. Instead he was led into the difficult aspects of Breivik’s childhood, not least via Breivik’s own manifesto that reveals a hatred for women and beliefs that motherhood should be reduced to use of artificial reproduction methods and that fathers should have custody of children when parents break up.

Breivik himself has claimed he had a good childhood and has consistently refused to talk about it, according to lawyers and police. His mother has remained mostly in isolation since his arrest and her state-appointed lawyer has said she won’t comment on the new book. Some media officials in Norway are themselves uncomfortable with all the details about her and her family that now are coming out, citing ethical press guidelines aimed at respecting privacy of third parties (in this case, members of Breivik’s family) even in highly public issues.

Both Borchgrevink, his editors at Gyldendal and many others defend the disclosures. “It’s interesting that the (Norwegian) press has been so careful with these details, and in one way it’s fine,” Borchgrevink told Dagsavisen. “At the same time, I think (the details) are so central in understanding Breivik’s hate that they had to come out. The public’s need for insight is more important than personal privacy.”

More signs of failure to respond

The book also raises questions about whether another area of public responsibility – state child protectives services (Barnevernet) – failed to do its job like the police and those responsible for emergency preparedness have been accused of doing. State psychiatrists, according to the book, were disappointed that neither Barnevernet nor the court followed up on their recommendation to remove Breivik from his mother’s care. She insisted on retaining custody, Breivik’s diplomat father was living abroad and the family received only minimal monitoring and assistance. Breivik’s father cut all contact with his son when he was 15 and told reporters shortly after his son’s attacks last year that he wished Breivik had committed suicide. “His father was pre-occupied with his own fate, that he’d have to live with his son’s actions for the rest of his own life,” Jerrold Post, a professor of psychology at George Washington University in the US, told Morgenbladet. “That was a rather self-centered commentary, so it seems to me that there’s been problematic parenting on both sides.”

Borchgrevink agrees. “Blaming everything on his mother is a primitive clarification,” he told Dagsavisen. “The mother was confused, scared and unstable, and sought help. The help she and her son received was inadequate. And the father wasn’t around.”

Views and News from Norway/Nina Berglund

Please support our news service. Readers in Norway can use our donor account. Our international readers can click on our “Donate” button: