Thousands of Norwegians lined up during the weekend to get a unique look inside what used to be the hub of their state government. The future of the bombed-out buildings that made up the government complex is uncertain, but its high-rise centerpiece remains structurally sound, and determined preservationists want to keep the wreckers’ ball away.

Known as Høyblokken, the building housed the Justice Ministry on floors two to 12 and the Office of the Prime Minister from the 13th to 17th, until an ultra-right-wing terrorist’s bomb went off on July 22, 2011. The explosion killed eight people, injured and traumatized scores more and forced the relocation of government ministries that now are scattered around the city.

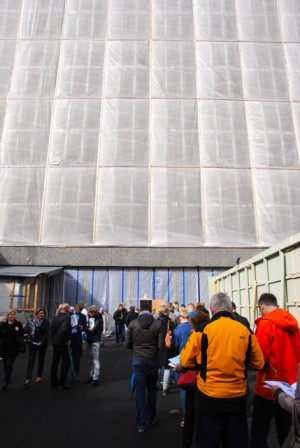

On Saturday and Sunday, the state agency in charge of state property, Statsbygg, unlocked the gutted remains of the building as part of an “Oslo Open House” event, and public interest was enormous. Crowds were so large that Statsbygg extended the opening hours both days and still had to turn hordes of people away.

Those lucky enough to secure a ticket for an allotted time frame (groups of 25 were allowed all the way up to the top floor every 10 minutes) got an extraordinary chance to wander through what’s now a mostly empty shell of the government headquarters that first opened in 1958, after more than 20 years on the drawing board. And they got to experience first-hand how a terrorist’s bomb failed to damage the building beyond repair.

Guides from Statsbygg could explain how the building has been secured and remains solid while it awaits a decision on its fate. Stair railings are twisted, elevators removed from their now-empty shafts, and most all the windows are gone on the lower floors, but the building’s integrated artworks designed by Pablo Picasso and Norwegian artist Carl Nesjar are intact and the top floors (where Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg had his office and could share panoramic views over Oslo with world leaders including US President Barack Obama) suffered minimal damage. Not even the windows shattered up there on the building’s west side.

A report from three architectural and consulting firms (Metier, Opak and LPO Arkitekter) has nonetheless recommended that Høyblokken be torn down, along with the adjacent “Y-blokka” that housed the education ministry, the “S-blokka” that housed the health ministry and the “R4-blokka” that housed the ministries of trade and oil and energy. The report, commissioned by the government ministry in charge of renewal and administration, recommended building a new complex in their place and expanding towards the east, buying up more nearby property so that all government ministries could be consolidated on the downtown site, within easy walking distance of the Parliament Building (Stortinget) and local courthouses.

The proposal to raze Høyblokken, though, has been met with strong protests from other architects, the state’s top official in charge of historic preservation and, most recently, journalist and author Hugo Lauritz Jenssen, who has just written a book detailing the building’s history and attributes. The building, viewed by some as a classic example of social democratic architecture from the post-war years when Norway’s social welfare state was being formed, “is so exciting that it must be allowed to stand,” Jenssen told newspaper Aftenposten last week. “It’s a building that reflects its time and has a much richer history than just its architectural history.”

Others see the building as ugly and outdated, and that the state now has a perfect chance to “think new” and build an entirely new complex for the next century. Tearing down the bombed buildings and starting fresh, the architectural consultants argue, will also be more cost-efficient.

One Statsbygg official who served as a guide on Sunday stressed that neither he nor his colleagues were supposed to have any official opinions themselves, but he said that personally, he hopes the building will be preserved. Its hollow shell still offers the chance to “start fresh” regarding interior design and technological infrastructure, and the building has a strong “symbol effect,” he said. Leaving it in place, some feel, will send a message that the terrorist didn’t succeed in his destructive rampage.

Guides could also relate anecdotes about how the building’s employee canteen on the first floor was just about to be renovated itself when the bomb went off just 20 meters away. The crews hired to start the work were supposed to have arrived at 3pm that fateful Friday and work through the weekend, but were delayed and thus not there when the blast surely would have killed them all.

The protests over the proposal to tear down the bombed buildings has prompted another government ministry responsible for environmental protect (Miljøverndepartment) to commission an extra report to be compiled by the historic preservation agency Riksantikvaren. Its leader, Jørn Holme, has said his agency, Statsbygg and the ministry had agreed before the bombing that Høyblokken should be placed under an historic preservation order (fredning). That hadn’t happened by the time of the bombing, but Holme hopes the government will preserve it now, for the historical and cultural reasons his report is expected to produce.

“It’s important that the first report be supplemented with advice from the state’s own agencies,” Holme told Aftenposten. “If the government makes a decision only based on the report now standing, it will be a scandal.”

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund