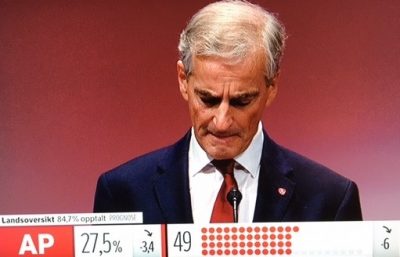

“For (Labour Party leader) Jonas Gahr Støre, this is worse than losing the election,” wrote one of Norway’s leading political commentators, Kjetil B Alstadheim, in newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN) on Thursday. He was referring to an allegedly “poisonous culture” within the party that’s now led to a loss of confidence in top party administrators.

The unrest has already been linked to a simmering power struggle between Labour’s more left-wing faction, fronted by the party’s deputy leader Trond Giske, and the more conservative faction led by Støre and co-deputy leader Hadia Tajik.

Giske has now become the target of at least four new allegations of “inappropriate behaviour.” Several of the women reportedly have avoided taking their concerns and complaints to the party’s top administrator, Labour Secretary Kjersti Stenseng, and gone straight to Støre instead. They reportedly view Stenseng, along with Labour MP Anniken Huitfeldt, as allied with Giske, and feared their complaints wouldn’t be taken seriously.

Stenseng vigorously denies the mostly anonymous complaints about Giske and herself. “All complaints will be addressed,” she told Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK) Thursday morning. She later blamed reports in a variety of media outlets in Norway about the complaints of alleged sexual harassment, claiming they have created an impression that Labour isn’t taking them seriously.

“If they (whistle blowers) feel they can’t come to me, I think that’s very sad,” Stenseng told NRK. “When rumours of sexual harassment have been connected to any power struggle, it raises the threshold for people to speak out. I think it scares folks, and that’s also very sad.”

It’s far from just the media sounding alarms, however. On Wednesday, seven top politicians within Labour’s Oslo chapter issued a written declaration of the so-called “poisonous party culture.” Marianne Hansen, who’s part of the City of Oslo’s also-embattled Labour-led government, told NRK that party leaders in Oslo “had received feedback from (party) members that there was uncertainty around whether it was acceptable to speak out about harassment. They didn’t want to be suspected of being part of a power struggle. We felt it was necessary (for party managers) to say that there is a low threshold (for reporting harassment) and that everyone should be taken seriously.”

Frode Jacobsen, leader of Labour’s Oslo chapter, said the party was in “despair” and he agreed there was a need to remove all doubt over how easy it is, and should be, to speak up about sexual harassment.

Both Stenseng and Huitfeldt have been accused of sowing the doubt themselves, by allegedly not taking initial complaints about Giske seriously. They reportedly were the ones who suggested the complaints against Giske were part of a power struggle to discredit him. Neither Stenseng, Huitfeldt nor Giske will comment on the complaints, or even whether they’ve been filed.

Støre is left to lead the party of yet another crisis, with DN reporting that he intended to “call Giske in on the carpet” and confront him with the allegations that reportedly came directly to him. Støre wouldn’t comment. DN reported that the new complaints about Giske come from women with central roles in the party, and that they’ve told their stories to Støre.

“It’s dramatic enough that Støre has chosen to call in his own deputy leader Giske … to take up the complaints he’s received,” Alstadheim wrote on Thursday. He called the reluctance of whistle blowers to go through Stenseng, as is customary, “evidence of a total lack of confidence” in party leadership, which is made up of Støre, Giske, Tajik and Stenseng.

Political experts are thus closely watching how Støre tackles this latest leadership challenge, after a long, difficult year. “It can determine both his own future as party leader and what sores the conflict can inflict on the party,” Alstadheim wrote. “This isn’t just about Giske’s future in politics. It’s also about Støre’s.”

newsinenglish.no/Nina Berglund