It’s being called the beginning of the end of the oil age in Norway: State oil and energy company Equinor’s decision to put development of a highly contested Arctic oil field on ice is being celebrated by climate and environmental advocates and mourned by industry, but may spark a boom in alternative energy projects.

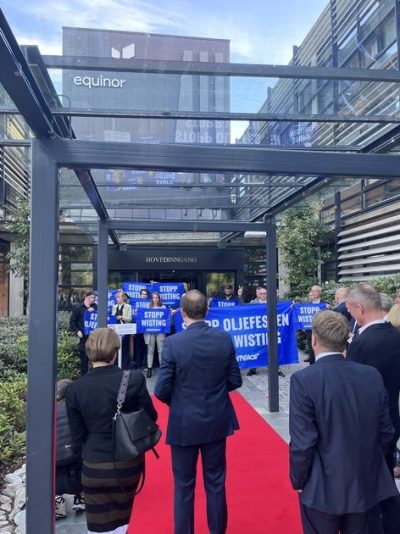

Critics of the project had called it “a climate bomb” that ignited widespread protests and was also challenged by the state environmental directorate. It issued what its own leader called some of the “most critical comments” the directorate had ever made.

“This is the most northerly development on the Norwegian Continental Shelf ever, in an area with highly vulnerable nature,” Ellen Hambro, chief of Norway’s Miljødirektoratet, told newspaper Dagens Næringsliv (DN) last spring. She and her colleagues demanded even more detailed information from Equinor and its partners (AkerBP, Petoro and INPEX Idemitsu), and still weren’t satisfied with their response in October.

All of the country’s environmental and climate organizations had opposed the project as have several political parties in Parliament and the youth organization of the Labour Party, which leads Norway’s unpopular minority government coalition. The Socialist Left Party (SV) intended to demand a halt to Wisting as part of its demands in state budjet negotiations. The Labour-Center government coalition must rely on SV to get its equally unpopular budget through Parliament.

Astrid Hoem, leader of Labour’s youth organization AUF, had promised “a major battle” over Wisting, likening it to the successful battle to prevent oil exploration in the rich fishing area off the scenic coast of Lofoten, Vesterålen and Senja in Northern Norway. That battle was won and Equinor found itself under huge pressure again over Wisting, which is located much deeper into the sensitive Arctic, around 300 kilometers north of Hammerfest.

The opposition wasn’t only over the climate and environmental risks involved but also economic risks to Norwegian taxpayers. Equinor itself had already determined the field to be so expensive to develop that it wouldn’t be profitable, and it was revived only by controversial tax incentives for the oil industry approved by Parliament during the Corona crisis in 2020. Wisting would also need to be powered by electricity from land, part of a climate compromise. That added not only to future operating expenses but potentially higher electricity rates for Norwegian consumers.

Now Equinor has determined that even with tax incentives, the project would demand investment of NOK 104 billion (USD 10 billion), much more than an earlier estimate of up to NOK 75 billion. “Global inflation and challenges in the energy markets because of the war in Ukraine” have created “capacity challenges and bottlenecks among international and Norwegian suppliers,” stated Equinor in a press release on Thursday. Equinor thus viewed the sheer economics of the Wisting project as unfavourable, and announced it would “postpone the investment decision” expected in December until the end of 2026.

Opponents were jubilant, but also chided Equinor, which had claimed just a week earlier that the environment would tolerate Wisting. Many criticized Equinor for not acknowledging the climate and environmental risks that Wisting posed, from carbon emissions and potential spills to threatening seabirds and fishing. Several claimed Wisting was postponed for the wrong reasons, with Equinor worried much more about profits than the environment.

The critics are encouraged, though, by several oil industry analysts who don’t think Wisting will be revived again. They point out that the field’s developers will lose tax incentives by not committing to the project by the end of this year, while costs are likely to continue to rise. They doubt Wisting will ever be profitable, even though the field is estimated to contain around 500 million barrels of oil equivalents at a time when Europe needs gas and other forms of energy.

The Wisting “postponement” thus may free up capital and trigger other alternative energy projects that are more needed than ever after Russia invaded Ukraine. Some see a major shift now away from investment in more fossil fuel projects and towards renewable energy from windmills at sea and solar power projects. Equinor is already involved in such, but criticized for being too slow with a green restructuring.

“Changing Norwegian oil policy radically and halting the Wisting project is an important issue for us,” Lars Haltbrekken, a long-time environmentalist who became an elected Member of Parliament for SV, told Norwegian Broadcasting (NRK). Now his party is not only free to fight on other fronts in its state budget negotiations but also push for more green investment.

Norway’s chapter of the World Wildlife Fund WWF even thinks the postponement of such a major Arctic oil project can be part of “a powerful signal” from the current UN climate talks “that giving up fossil energy is the key to fighting climate change.” Karoline Andaur, leader of WWF in Norway, was also critical to Equinor’s emphasis on economics over climate concerns when announcing its Wisting postponement.

“As long as Equinor’s decision is a consequence of higher costs, and not made out of consideration for the climate, it won’t do much to change the impression that Norway speaks with two tongues,” Andaur told newspaper Dagsavisen. Norway has long been accused of hypocrisy, in mounting a climate-friendly image while continuing to search for and produce oil.

Gina Gylver, leader of Natur og Ungdom, was among those celebrating the most, though. She’s certain that Equinor’s “postponement” really amounts to the project being scrapped, as is Truls Gulowsen, leader of Norway’s chapter of Friends of the Earth (Naturvernforbundett).

“This is a great victory for everyone who’s concerned about the climate and environment,” Gulowsen said. “The time for developing new, big oil fields is over. We are convinced this is the last nail in the coffin for this horrible project.”

NewsinEnglish.no/Nina Berglund